Genre to Medium – You Heard if from an Expert

It’s hard to get a decent bead on the current state of health of the broader documentary form. Perhaps somebody should make a documentary about it. On balance, there seems to be a kind of ‘best of times, worst of times’ sense among the commentariat and the community of makers.

In an extremely enlightening piece on Indie Wire dissecting the current state of play in the documentary world, Eric Kohn kicks off with a Guillermo del Toro cri-de-coeur about – of all things – animation.

“Animation is not a genre, it’s a medium,” thunders del Toro, talking during the release of his animated feature Pinocchio, Kohn makes the point that ‘documentary’ should start thinking the same way about itself to avoid being sidelined under a tag that automatically marginalises it in the marketplace. Discovering that quote represents the precise moment this piece veered off the original plan of dissecting the biggest mistakes documentary filmmakers are known to make. Perhaps next year?

Kohn makes a compelling argument but much of it centres around there not just being a ‘marketplace’ for documentary but also the nature of that marketplace – and the marketplace par-prominance is Netflix….. apparently.

On one reading that sure seems to be the case. The most cursory of rundowns of the Netflix offering and the accompanying budgets paint a healthy, or at least rosy, picture. But writing on hyperallergic.com, Jake Pitre persuasively makes the point that Netflix’s documentary offering tends to fall into just a couple of categories; “true crime and infotainment explainers”.

On one level, what’s the harm? Nobody has to watch these films if they’re not their thing and in the meantime films are getting made, filmmakers are getting proper budgets to work with, crews are employed and stories are being told.

But every big ship creates a heck of a bow wave. In a detailed and thoughtful piece on vulture.com New York Magazine features writer Reeves Wiedeman takes a look at the front of that boat. He quotes Dan Cogan, the co-founder of an independent documentary production studio in New York called ‘Impact Partners’ who outlines the way the documentary market is being changed by all of this.

“Once it became clear documentaries could sell for $20 million or you could get a $5 million budget, all the buyers wanted them to be at that level,” Cogan said. “The smaller films, the more visionary films that were exciting to all of us — those became the films that people were less interested in. Once something looks commercial, that’s all people want it to be.”

When Wiedeman put that assessment to a spokesperson at Netflix, the response was at least simple and straight forward. “It’s not enough to do something that a few million people might really love when you’re trying to reach 25 million people or 50 million people,” they said. “A lot of documentaries — I would say the majority of documentaries — don’t meet that bar.”

OK, but Netflix will never show some kinds of documentaries and the overwhelming number of film and doco festivals will never show the kind of work that runs on Netflix. Surely that describes a happy, if unequal, equilibrium. But on documentary.org making the case that Netflix might be the 600lb gorilla and the room, Robert Bahar delivers a superbly researched assessment of where the plethora of indie docs are (or aren’t) landing when it comes to that critical moment when somebody has to come on board and take them onwards to the outside world. Suffice to say, great and intriguing docs are being made and are being screened at incredible and committed festivals but the numbers that get the necessary wind in their sails so that they can get some wind in their sales is only going in one direction – and that direction ain’t up.

Then there is the world of independent animated documentaries. A comparative analysis of documentary festivals shows the number of animated docs featuring in them all slowly declining year on year over the last decade except for 2019. Animated feature length docos of the Waltz With Bashir strain remain unicorns and yet we talk annually to filmmakers who claim to have an animated doc in development. Few seem to emerge but the steady stream of well-crafted and inventive short animated docs remains a steady one. Netflix is yet to really stumble upon this treasure trove so in the meantime LIAF stands ready, willing and able to fight the good fight with our annual programme showcasing the latest work from the community representing the medium of animated documentary.

The short form animated documentary tends to encourage a lean towards certain styles of stories being told in ways that are best likely to work in this ‘medium’. The unique properties of animation attract people who tend to conceive films utilising these properties and the shortness of the finished films makes some types of storytelling more viable than if it were to be undertaken in a feature length production.

Hence we tend to see a number of films, for example, that bring together the voices of a number of people with a different slant on a specific topic. Edited interviews of these participants are usually the kick-off point and the animation is used to bring those stories to life and lift them beyond what the purely literal or representational imagery of live action cinema is capable of doing.

The programme opens with a striking example of exactly this. Better Man by Czech animator Eliška Jirásková opens vibrant and loud in a world of gyms, bodybuilding and increasingly complex discussions about body awareness and tales of what has led these people to take this direction. It often uses some very clever multi or split screening design effects as a device to meld the recollected historical story with the depicted real-day reality. And bringing a rolling superhero motif into the mix not only anchors the action but spreads a more nuanced layer of questioning across the culture of what is being shown.

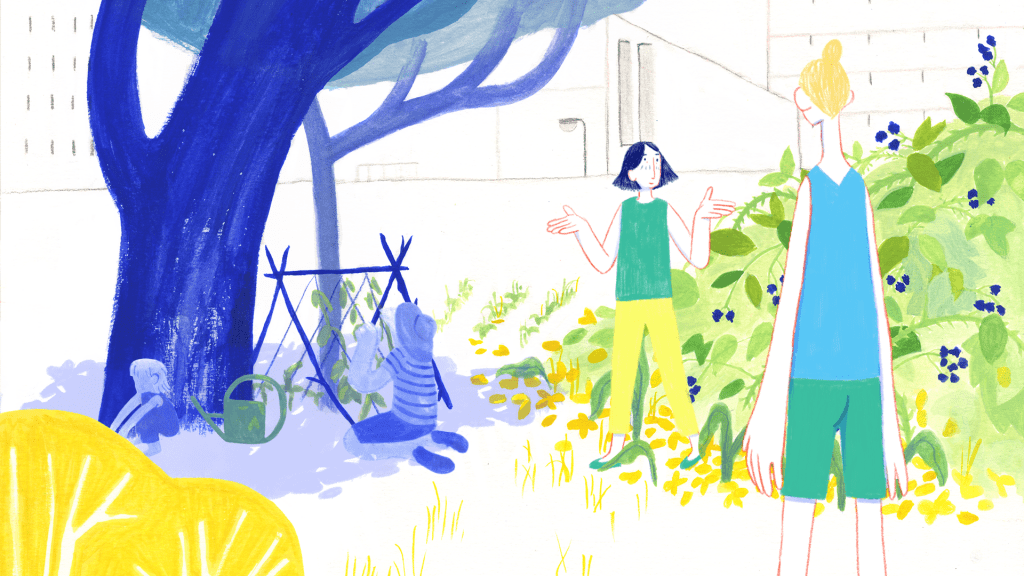

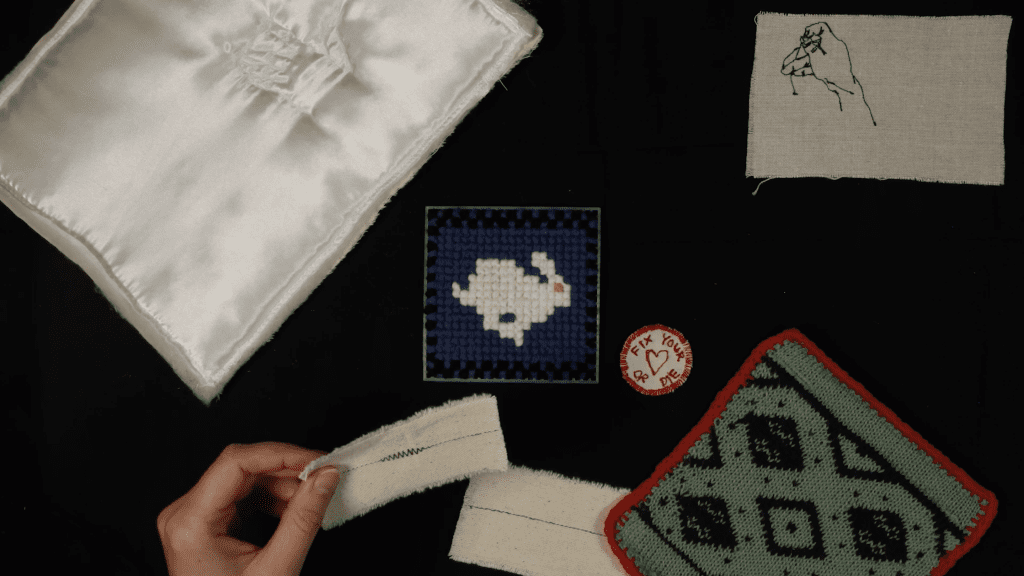

The use of recorded interviews is also the lead point for a number of other films in the programme. Mealitancy (Marie Royer, Zinia Scorier), On Hannah Fields (Lewis Heriz), Warp and Weft (Isolda Milenkovic) and Strokes Of Wildflowers (Livvy Seabrook-Wilkins) each take this path, albeit using very different approaches to the visuality of their films. Mealitancy goes for strong, colourful and vigorous art design as a perfect match for the energy and determination of the characters and their commitment to their cause. On Hannah Fields immediately heads off in the exact opposite direction, holding to a black and white photo-real look for much of the animation, sometimes allowing that to morph almost into the abstract. This seems like a counter-intuitive way to celebrate outdoor gardens which would usually attract a colour palette to match as a default design assumption, but the bigger purpose the filmmakers seem to want to get across is the sense of peace and calm these gardens offer and this more subdued visual approach suddenly makes sense. Warp And Weft makes the ‘medium the message’ by using the very handcrafts being discussed as the animated characters of their moving discourse on the sometimes somewhat fractious relationship between arts and crafts. And Strokes Of Wildflowers opts for a more deliberately classic and stylish drawn look to match the aura of the people it is depicting as they recount the experience and aftermath of a key turning point in their life stories.

In a similar vein, but with a necessarily sharper focus are the films that use the recorded testimony of a single character who has something to share. As often as not these are particularly personal stories and they can run the gamut from trauma (of which, more shortly) through to periods of inquiry and indecision and on to singularly uplifting experiences. Azkena by Spanish animating duo Ane Inés Landeta and Lorea Lyons is a perfect example of this and adroitly uses a fascinating range of differing techniques to match the varying stages of the main character’s quest for an understanding of her past as she moves towards a time when she must make some key decisions that will shape her future.

Klára Kubenková, on the other hand, with Polio holds to a singular bold style, relying more on an extremely clever recurring motif to accompany and accentuate one woman’s experience of living life in the wake of having had polio.

Animation has often been used to depict situations or victims of trauma. As a medium it helps soften the blow that trauma, by definition, delivers whilst allowing ‘easier’ or softer ways to show people caught in devastating positions. It helps, for example, get across that the sometimes overt violence that can be readily depicted is not actually the worst wound that is inflicted with the lacerating of the psyche being more profound and something better represented with the more imaginative powers of animation. A gold-standard example of exactly this is Tereza Nebe Motýlová’s A Tiny Film About Rape. The hint, as they say, is in the title but the impact floats over to us on the vapour of the stylised animation within the film, it’s look, pacing and impact ebbing and flowing as the emotional jigsaw puzzle of the story is pieced together with an inconsistency that matches the messiness of real life, the emotions of the teller and the patchwork nature of memory.

The Mustached Clown Circus by Ana Comes, Tomas Alzogaray Vanella and Paz Bloj does not offer the commentary of a personal participant in the story and the story itself is so eerie it borders on the mythical but horror and trauma enjoy an almost infinite number of forms and here the filmmakers have doubled down on the creepiest and most uncanny attributes attributed to the notions of ‘circus’ to quietly ramp up the sense of the dread that sits in the middle of it.

A couple of fairly insightful – not to mention funny – ‘meta-animation’ films found a ready home in this year’s Animated Docs programme as well. Any animator will have their own stories of the dubious joys of funding applications and form filling. That scenario is common enough but when it is compounded by a pressure to bang your round peg of an idea into a square hole of a border-line irrelevant criteria, the blood pressure goes up and google searches for the nearest off-licence seems like an entirely legitimate reflexive response. Years ago (like before some you were born), legendary American indie animator Don Hertzfeldt made a film called Rejected about the experiences of entering – and being rejected by – film festivals, something that paradoxically I don’t think Mr Hertzfeldt had that much experience of coz his films screened everywhere. It hadn’t really occurred that Rejected was a documentary until Biting The Hand That Feeds You by Chantal Peten popped up. About as meta as you get, it’s a film about applying for funding to make a film and for those of us who have visited that dusty, breezy zone the grim humour takes a stronger hold as the film progresses to its ultimate conclusion. Oh, and by the way, here at LIAF HQ, we reckon you’re REALLY funny Chantal, don’t take any notice of what they say.

And as legendary as the British film Great (1975) is, there will be plenty among us who have never heard its director, Bob Godfrey speak nor have a sense of the playful nature of his persona. ‘Great’ was the first British film to win an Oscar and Godfrey sits as a bona fide legend of the British animation scene with a new film called I Am A Rebel by Martin Pickles, a timely reminder of the man, the film and the legend of both. Godfrey’s personality pours out of the narration and Pickles uses every trick in the animation playbook to ensure the visuals keep up. It is the perfect fusion of subject and substance with a rounding layer of beautifully animated style to top it all off. And it’s a chance to revisit a couple of touchstones of British animation.

The programme ends with an extraordinarily powerful example of what animation is capable of when all the taps are turned on. Winter In March by Natalia Mirzoyan says what it means and means what it says. It arrives as a fully formed, empowered testament to Mirzoyan’s opposition to the Russian invasion of Ukraine. It is her statement that this is not OK, that being powerless in the face of this event does not equal being voiceless and that saying nothing is not an option.

“Living in St. Petersburg at that time, I felt a deep sense of responsibility for what was happening but had no idea what I could do,” explains Mirzoyan. “All protests were harshly suppressed, and the most dreadful feeling was the sense of helplessness—that I couldn’t change anything or have any impact.

“Later, I left Russia and moved to Armenia, my country of birth. There, I met my friends from Russia who, like me, opposed the war and had fled their country due to their inability to influence the situation, as well as fear of arrests and mobilisation.”

The response was to interview some of them and their stories became the angry fabric that she has used to paint Winter In March on to. It is documentary, drama, warning and call-to-arms all rolled into one.

The short animated documentary form seems to be in fine form if this programme is anything to go by, perhaps buffeted a little by the forces roiling the more commercial end of the doco industry but also sitting off to one side of the worst of those tides, happily going about its own business. As long as animated docs this good continue to get made, LIAF will happily show them.

And as for the 10 Mistakes Documentary Filmmakers make? Why wait til next year when Raindance has already covered it so well.

Malcolm Turner

International Competition Programme 7: Animated Documentaries screens at The Garden Cinema Sat 6 Dec and online from the same date (available for 48 hours)

Leave a Reply