Fair to say that people have been using the tools and methodologies of art as a platform for documentary making as long as they’ve been scratching images into rock walls. Cinema, one of humankind’s youngest artforms, was arguably delivered into the world as a documentary form when the Lumiere brothers screened The Arrival Of A Train At la Ciotat Station in late 1895, a film which used all 50 seconds of its run time to depict an unbroken scene of – well – a train arriving at Ciotat Station. Without a script or editing of any kind it was also arguably the last literal documentary, giving way to a trend that would see documentary filmmakers manipulate their footage to craft the version of reality that best suited their purposes. And, at the same moment in history, tales of terrified audience members running from the cinema as the projected image of the train bore down on them also marks the first known instance of film industry PR BS.

Animation eventually followed suit. The most famous early example, of course, is The Sinking Of The Lusitania, Winsor McCay’s 1918 ground-breaking – but ultimately futile – effort to convince the American public to join in World War I by rendering in fine grain detail the infamous incident of a German U-Boat firing on and sinking a civilian passenger liner off the coast of Ireland with the loss of more than 1,100 people.

Muybridge’s famous galloping horse sequence could plausibly be termed animation of a sort and at least ‘documentary-ish’ in as much as it was made to prove a point that all four of a horse’s hooves are off the ground at a certain moment in the gallop cycle.

Lesser known is the 1923 sub-classic, 20-minute The Einstein Theory Of Relativity animated by one Dave Fleischer, of Fleischer Brothers fame. It’s an earnest attempt using animated bullets and moving diorama of the planets to explain how – among other things – Einstein’s magic theory can be used to depict a man being shot back far enough in time as to be able to witness Colombus’ arrival in the “new world” (at the time, it was actually the same ol’ old world to the people that had been living there up to that point).

The early history of some important animation studies was built on a foundation of documentary and instructional filmmaking. Here in the UK, the iconic Halas & Batchelor Studio got its start, in part, by making commissioned films about gardening, recycling and topics intended to improve morale as the war began to grip British society.

Over in the United States, the venerable UPA (or United Productions of America) were making films warning US fighter pilots against undertaking risky or needlessly showy manoeuvres along with other US military instructional and informational films. Check out Flat Hatting from 1946. Their far more substantive Brotherhood Of Man (also 1946), funded by the United Auto Workers union to help foster better race relations in society in general and in the workplace in particular is probably a documentary, or at least has strong traces of doco DNA flowing through its veins. Later, in 1964, John Hubley, by then working independently of UPA with his wife Faith Hubley, would release Of Stars And Men based on a book by the same name looking to explore the place of humans in the universe written by the social activist and astronomer Harlow Shapley, who also narrated it.

Uncle Walt had little hesitation about pimping out his leading stars as spokes-animals for a range of doco and doco-flavoured films. A classic of the sub-genre has to be The New Spirit (1942) which sees a normally irascible Donald Duck practically cock-a-hoop with positive excitement about the opportunity to fill in the new American tax form. In 1955 Ward Kimball, one of Disney’s most acclaimed directors of all time, not only directed but introduced and narrated a surprisingly detailed history of rockets for a film about the coming era of space travel called Man In Space (1955). Highly watchable, even to this day. Kimball also directed the Oscar winning Toot, Whistle, Plunk and Boom (1953) which doesn’t really intend to be a documentary but sort of can’t help itself as it uses a dreadful (or at least deeply irritating) song as the basis for a melodious treatise into the history of four different types of musical instruments. It was also one of the very few Disney excursions into the area of ‘minimalist’ animation which was being championed by UPA at the time and showed all signs of becoming the dominant animation style of its age, especially as TV began taking hold in the USA. Interestingly, Disney also began alerting us to the potential risk of climate change in Eyes In Outer Space (1955) although he thought it was the Russians who were responsible. Annnnnnd Disney’s 1946 The Story of Menstruation is one you don’t hear about much these days either – but it’s out there, in more ways than one.

Often overlooked is the fact that Norman McLaren’s classic film Neighbours (1952), arguably his defining film, won the Oscar not in an animation category but for ‘Best Documentary Short Film’.

A couple of odd-bod favourite entries into the Animated Doc Hall of Fame before we take a closer look at how the form is travelling at the moment.

Earlier this year we lost an Australian animator and cartoonist by the name of Bruce Petty. His 1976 film Leisure is an astonishing, densely realised, imaginatively designed history of leisure and its changing relationship with humanity down through the ages, and beyond. Hyper-montage would be the best way to describe the style – the sheer volume of work to create it must have been extraordinary. It deserved the Oscar that it won (albeit credited to the film’s producer Suzanne Baker) beating out, among others, Caroline Leaf’s The Street.

And, finally, when the mood takes you go hunt down American History made in 1992 by Trey Parker…. yep, Trey Parker of ‘South Park’ fame, that Trey Parker! Perhaps channeling a little of his inner Kaspar Jancis, one night he sat down his Japanese roommate, had him freestyle his version of American history into a dictaphone and then he animated the resulting soundtrack. While this might not be the ‘official’ version of American History it’s one version, and in the end all documentaries are at least a little subjective.

There is nothing quite like that in this year’s ‘Animated Documentaries‘ but LIAF regulars will not be surprised to learn that the flow of inquisitive and fascinatingly original animated docs continues unabated. Diverse is the word – the spread of subjects represented in the programme this year would have to be one of the broadest slates we have ever run in this category! There are films covering contemporary matters such as environmental issues, the chaos surrounding the near-lawless drug culture in Mexico and the impacts of compulsory hijab wearing in Iranian schools across the scale to historical stories covering long cold criminal cases, vivid recollections of the German invasion of Poland in the lead-up to WWII all intermingled with more personal reflections on such things as the harrowing aftermath of a brutal attack to the more creative observations surrounding old school filmmaking, the mental health benefits of handicrafts and the positive role music plays in many of our lives.

The techniques and styles employed by this range of films are as equally diverse and remarkable!

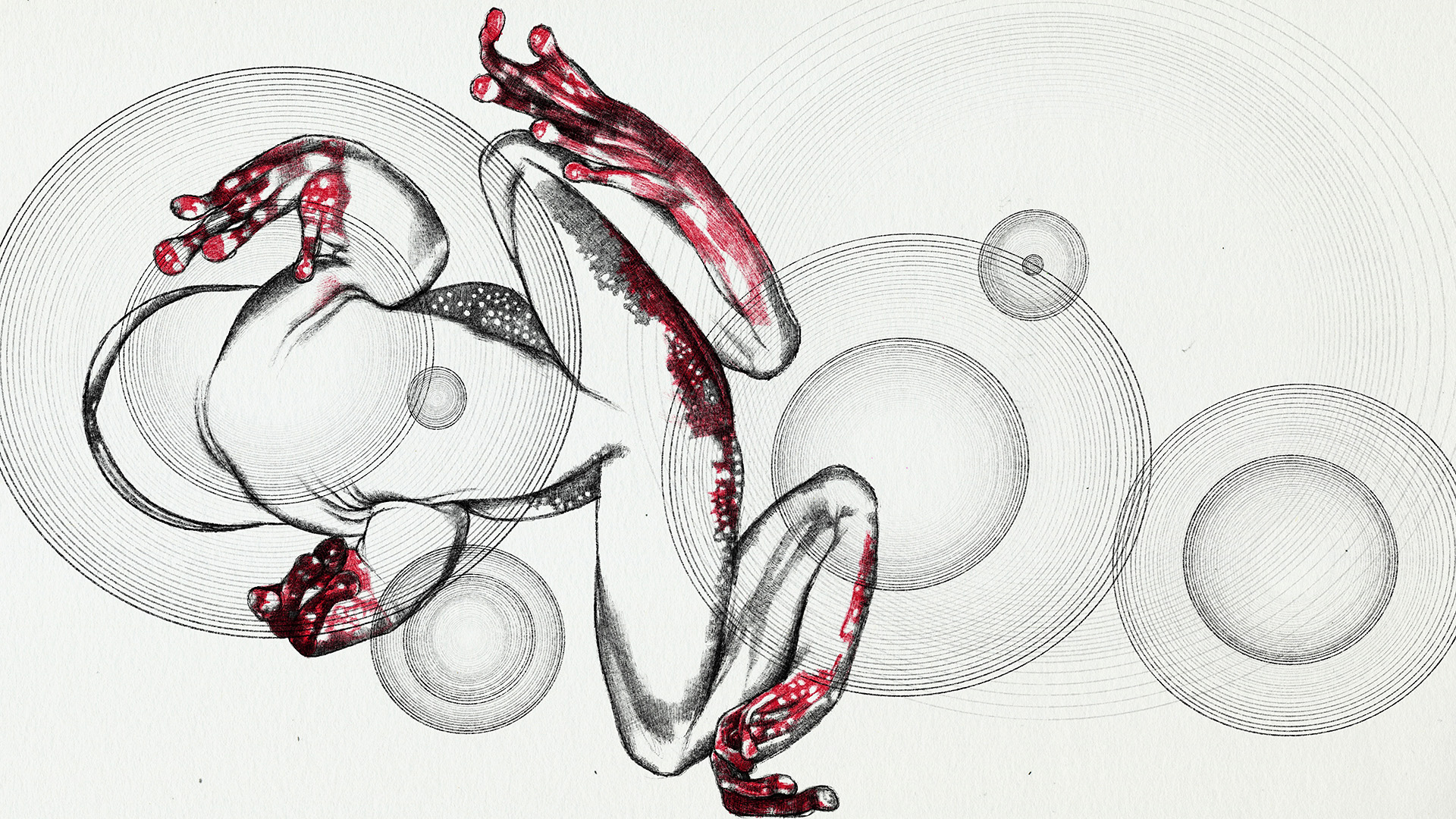

The programme opens with a simply exquisitely animated exposé looking at the shock disappearance of a particular type of frog from the luscious environment it had once thrived in in Costa Rica. The Waiting is animated by German designer and animator Volker Schlecht but is told through the eyes and with the voice of Karen Lips, the researcher who had dedicated several years to its study. Cleverly, it presents almost in the style of a crime drama or ‘whodunnit’. The animation is as intricately rendered as it is beautifully descriptive, showing us not just the subjects of the film but using a plethora of imaginative morphs and visually poetic scene changes to take us into the ever changing, ever evolving, always moving essence of this vast, magnificent living organism; one in which all its constituent parts are always in simultaneous unity and opposition. Essentially hand drawn, this incredibly imaginative use of the unique properties of animation bring to the screen a more complete, more nuanced, more sensorially vivid immersion into this world than the most complex, expensive live action cameras ever could.

On the other hand Doubt by Polish animators Adela Krizovenska and Ondrej Vomocil brings a more obvious digital and 3D style to bear, albeit one that fractures into a varied range of visual designs to demarcate the range of stories being told by the roster of people the film has drawn in to relate their own personal experiences relating to the core theme. A graduate film from FAMU, the main animation school in the Czech Republic, Doubt does a simply superb job of presenting a constantly moving, constantly shifting, constantly morphing carnival of images that somehow seem to always perfectly reflect the inner mood of the various and varied doubts being expressed by the narrators. In doing so, Krizovenska and Vomocil seem to have – almost by some kind of ephemeral osmosis – found a way to connect us directly not just with the words being spoken but the feelings they are trying to express. Good luck trying to pull this trick off by simply pointing a live action camera at each subject and hoping to capture that inner kernel of core truth.

And then there are the filmmakers who have brought elements of the physical world into the ingredients list of their films. This ‘blended’ approach to animation is as old as the artform itself and although many of the tools of the trade have changed, the impulse and the sense of watching ‘real’ materials be brought to life is an ageless one.

Handmade Happiness by Australian (Tasmanian in fact) animator Vivien Mason is a prime example. The genesis for the film was an article Mason read about the mental health benefits of making handicrafts, be it knitting, crochet, pottery or working more abstractly with various fibres. Mason fashioned a cast of characters out of some of these materials and pressed them into service to present the recorded words of some people she interviewed who were finding their own peace and solace by working with their hands.

Our Uniform by Iranian animator Yegane Moghaddam carries a more sinister message about the compulsory wearing of the hijab in Iranian classrooms but also uses real fabrics and fibres as its main animating materials. In this case though, the fabrics act as more of a canvas into which is digitally ‘painted’ much of the action and many of the characters. But in a film that is about a specific form of material (a hijab), it serves as a visual motif and reminder of the foundational source code of the film, always there reminding us what the film is about at a molecular level as the literal structure of the story plays out front and centre in words and pictures. It’s a bold and fascinating creative choice and helps to draw the viewer into the film.

And the programme finishes with a captivating piece of meta-film / meta-animation reverse engineering. In On Film Emma Hough Hobbs explores her old school passion for the fragile and mercurial beauty of real film. In On Film she and her narrators have taken advantage of the best of both worlds, creating much of the imagery with digital devices before transferring the finished layers onto 16mm film stock – a kind of reverse engineering that in a strange, inverted way captures and utilises the best properties of each of these disparate mediums.

Putting it at the end of the programme sends you all out into the night with the gentlest of reminders that, at the end of the day, beyond subject material and beyond genre and technique, the core mission of each and every one of our competition programmes – ‘Animated Documentaries’ no less than any other – we’re here to celebrate great animation and the work of people who think like animators. Seeing this so successfully applied to such a specific genre (or sub-genre of animation) speaks volumes not just for the skill and creativity of the animators but also for the bottomless potential for animation as an artform.

by Malcolm Turner

Animated Documentaries screens at The Garden Cinema and online Tue 28 Nov find out more

Leave a Reply