The Netherlands Institute for Animation Film (NIAf) is – or was – an utterly unique organisation. Officially opened in September 1993, NIAf was a curious hybrid, intensely focused on supporting animation as an artform through a number of different activities.

Join us for a celebration of the ‘is’ and the ‘was’ of the NIAf, Sat 5 Dec 15:00. Find out more

At Barbican book tickets

NIAf was the brainchild of legendary animator, Gerrit van Dijk, and was but one of a number of initiatives that this passionate advocate of Dutch animation more or less forced into being through the sheer strength of his will and the stamina of his labours. He and wife Cilia had already established a distribution office for Dutch animation but he recognised a need to provide a place where people could learn more about the craft of animation, the art of storytelling and have the space and re- sources to make their own films and experiment with their ideas. After gathering sufficient political support, NIAf was the eventual result.

At its core, however, was its focus on facilitating the production of short, auteur, animated films. This was its unshakable central mission. From the beginning, it set out to achieve this by becoming something that could perhaps be best described as a kind of school without a curriculum.

Animators, or those with a dedicated interest in animation and who had studied in a relevant discipline, applied for a position at NIAf. If successful, they received a grant and their own atelier (or study/studio space) and went on to spend the next two years learning their craft in the supportive, creatively charged atmosphere that NIAf provided. A ‘study program’ of sorts was constructed specifically for each of their needs and according to the demands of the animated project they were trying to complete. This meant the people studying and working at NIAf were essentially ‘Artists In Residence’ although ‘Participants’ is the preferred and official title.

Above and beyond this, NIAf created one of the largest research libraries on animation in the world; developed an extremely successful and efficient distribution arm to ensure that not just NIAf but many other Dutch films got out on to the international screening and festival circuits; and organised a simply astonishing roster of workshops by some of the most revered names in international animation.

In all, a staggering 110 workshops, over a period of 20 years, were staged at NIAf with names such as Priit Parn, Yuri Norstein, Phil Mulloy, Paul Driessen, Alexander Petrov, Chris Hinton and Suzie Templeton giving a hint as to the standard and diversity of these events.

So… every year, several experienced or aspiring animators each with a bold, personal project on their drawing board would be accepted into NIAf. They would each be given a grant substantial enough to help them achieve their goal and an atelier to work and study in. They had access to an incredibly rich research library and were the recipients of teaching and assistance programs tailored specifically for their needs. Several times a year they had the opportunity to take a master class lead by some of the best animators and animation technicians in the world. And their films, when completed, would be distributed on their behalf all around the world.

And yet, in November 2013 NIAf officially turned off the lights for the very last time and was no more. The work being produced there had never been better and, at the time of closing, no less than four top-rate productions were left in limbo, struggling to find another pathway to completion. All of NIAf’s other functions were, likewise, doing well. The number of Dutch animated short films being distributed by NIAf were increasingly finding their way into an ever expanding plethora of festivals; the research library continued to grow; and the NIAf Workshops program must have been the envy of almost any educational institute anywhere in the world.

So, what went wrong?

In a word, politics. The Netherlands, long famed as one of the most tolerant, politically laid-back societies in the world began to change in the aftermath of two high-profile and shocking assassinations.

Netherlands politician Pim Fortuyn had been assassinated during the 2002 election campaign. While his political platform of limiting Muslim immigration and curtailing most aspects of a multi-cultural society was one that few Dutch seemed to embrace at the time, the spectre of political assassination was utterly foreign and deeply shocking to the Dutch.

Less than two years later, filmmaker Theo van Gogh had, along with a Somalia-born collaborator, made a film criticising the treatment of women in Muslim societies. His reward was to be shot eight times, stabbed with two knives and partially decapitated in an Amsterdam street one morning on his way to work by an Islamic extremist (some say terrorist) who was eventually sentenced to life in prison.

Many believe that this was the beginning of, and provided the impetus for, a creeping nationalism to wend its way into Dutch politics. Parties of the far political right still gained little traction in the Dutch way of life but a more right-of-centre, simplistic, neo-conservatism became the order of the day. And with it came the election of governments that saw neither value in, nor the need to provide any support for, cultural institutions of almost all stripes. By 2010, a great many institutions had the writing on the wall writ large in front of them – funding will end soon, sink or swim.

Making qualitative arguments about the standard of the work produced, the invaluable need to conserve and create Dutch culture with all the value measurements that arts and cultural institutions stand on as gauges of their contribution and right to resources did not simply fall on deaf ears, they fell upon minds that could not grasp the meaning of the conversation.

NIAf was but one of many organisations that, ultimately, was never going to survive this form of socio-political purging. But it tried. Regional councils were lobbied and in some cases were initially supportive, wishing to retain the skills and cultural output that an organisation such as NIAf nurtures. In the end it was all to no avail, and on November 1st 2013, after 20 years in existence, NIAf officially called it a day.

NIAf had always been a very good friend to this festival. Annually, a package of wonderful Dutch animated short films would turn up like clockwork. They were, in so many ways, something of a one-stop shop that made keeping in touch with the latest Dutch animation a simple process. NIAf’s closure – particularly for the reasons that transpired – demands marking.

A retrospective is the best way to look back on what has been lost and wonder, without knowing, what future gems we might have been able to enjoy. But beyond the films that have been made and the films that will now not be made, are the people who created, ran and studied in NIAf over the years. What of their perspectives, reflections and experiences?

Time to get on a plane!

The obvious person to start with is Ton Crone, who took up the baton that was passed on by van Dijk. Crone had been there from the beginning and for twenty years had been the ‘hands-on’ person who had made it work, kept it afloat and overseen its growth and expansion.

Sitting comfortably in Amsterdam’s new and expansive home-to-all- things-cinematic, The EYE Institute, he has a soft yet certain gaze that gives the impression of a man staring all the way back through those twenty years. We both know that – somewhere – deep in the vaults of this vast and impressive building sit most of the films that NIAf produced. Perhaps not his entire life’s work but a fairly decent chunk of it and we sit and ponder the future of Dutch animation without NIAf.

“In the Netherlands I hope The EYE Institute will be inspired and recognise the importance of animation from the past and, even more importantly, of that being made today”, he says optimistically. “Our collection will help that.”

The EYE is, practically speaking, the only place in the Netherlands that could nowadays take NIAf’s films, ensure their safe keeping and make them available to anybody who wanted to screen them. That ticks some important boxes but it, perhaps critically, lacks the passionate advocacy for animation that was such an elemental part of NIAf’s kinetic energy.

Crone is better placed than anybody to try and explain how NIAf worked: what made it tick and how so many great films were produced there.

“We had no set curriculum”, he begins. “We made a programme based entirely on the person coming in as a participant. We looked for tutors based on what each participant needed. I was the producer and I dealt with the budget. But we gave them the responsibility of making their film. They had two years to learn all of these things. They needed to learn how to work with time – to make the most efficient use of time – and to learn the efficiency of being a storyteller. That was the greatest challenge to get across to them.”

For many, the assumption was that NIAf was based in Amsterdam. In fact, it was in Tilburg in the south of Holland.

“I was pleased to be in the south near Belgium and Germany and close to so many important institutions. It was an advantage”, he says with something approaching a wry smile. “I had the world before me but Amsterdam people think Tilburg is the end of the earth.”

Keeping the NIAf HQ ticking over for a good portion of its existence was Ursula Van Den Heuvel. She worked there for 14 years and her passion for NIAf is undimmed by its demise. In fact, she has been instrumental in forging many of the links that made this retrospective possible. She had never heard of NIAf until her job at the film archive in The Hague came to an abrupt end as a result of budget cutbacks. A friend mentioned NIAf needed help and she found herself re-employed. Such is life’s rich tapestry.

“On my first day, Ton just gave me a big pile of stuff to watch and read”, she says, looking back. “I really had no idea what this kind of animation was all about.”

A trial by fire was just around the corner. Michael Dudok de Wit’s film Father And Daughter took out the Academy Award not long after she started. NIAf was distributing it and the demand was almost overwhelming. In those days, everything was screened from either 35mm film prints or betacam tapes. Each of them had to be sent by courier and kept tracked of to ensure they were returned. A massive job. Inquiries and invitations exploded.

She looks back with particularly fond memories of being part of a team (including Mette Peters, Paul Moggré, Erik van Drunen and, of course Ton) that oversaw the development of NIAf’s incredible library. This library, one of the most extensive animation related libraries in the world, grew to encompass some 8,000 films and 2,200 books, magazines, clippings and articles. For the most part, this collection was dispersed around a number of Dutch film and culture organisations when NIAf closed, even the bulk of the substantial VHS tape collection which was taken up by the University of Groningen.

“It was great to have built that specialised library over the years”, she says. “It’s a pity that it couldn’t be saved as a whole, especially because that library collection was the only one about animation in The Netherlands. I always enjoyed it when visitors came to do research in our library and it was a pleasure to help them.”

Special tribute needs to be made to NIAf’s technical supervisor, Peter van de Zanden. His name is on virtually every film and his fingerprints will be on virtually every machine that came through NIAf’s doors in its 20-year history. Peter’s contribution to NIAf as a filmmaking organisation simply cannot be overstated and to this day when a digital copy of an old film is required or betacam deck to play an old tape has to be conjured up and coaxed into life it is him they turn to.

He was a vital part of making NIAf work when it was doing what it did best and he remains an equally vital part of preserving its legacy. At the end of the day though, NIAf is ultimately about the films and the filmmakers. They and their work are central to this story and there have been a good number of them pass through the doors of NIAf over the years. Let’s cast our eyes back …

Frodo Kuipers came to NIAf after studying at the KASK school in Belgium. He spent almost three years at NIAf and produced two films: Street (2005) and Shipwrecked (2005). He looks back on his time at NIAf with extremely fond memories and sees much of the experience as something of a luxury.

“The great thing about NIAf was that there was time and freedom to research and explore”, he says. “That was the whole idea. It was a place where everybody had an affinity with animation. It was a doorway to the rest of the animation world where you would meet great filmmakers that often you stayed in touch with. Where else could you do that?”

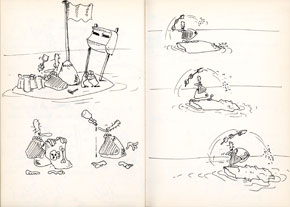

Kuipers’ Shipwrecked is a manically delightful study of the rotary logic of humans caught in rapidly changing circumstances and working to different priorities. Kuipers claims to have worked on the concept and storyboard for 18 months, although the film itself was made reasonably quickly. It is a classic!

Manic is also a good word to describe the work of Sjaak Rood. Originally a theatre lighting designer, Rood started experimenting with animation to enhance some of his theatre lighting designs. This morphed into further experimentation with interactive animation and, finally, a short film. He turned to NIAf as an opportunity to learn more about what to do with the animation skills he had been teaching himself as he went.

In person, he is a bundle of barely constrained energy. His films know no such restraint. Coffee (2012) and Fast Forward Little Red Riding Hood (2010) emerged from his time at NIAf. Coffee bears the unmistakeable stylistic influences of a master class given at NIAf by Canadian animator, Chris Hinton.

“I wanted to see just how sloppy I could do the artwork”, he offers. “You draw it in a certain way, at a certain speed and sometimes all those lines just begin to arrange themselves into a kind of accidental animation.”

Perhaps, but Coffee exudes an energy sufficient to power a small town! Its relentlessly changing visuality is a sandstorm on the screen and one wonders how this could have been storyboarded at all. But Rood possesses a creative imagination that can keep track of this blizzard of twitching imagery and marshal it all into a rowdy, somewhat coherent whole on the big screen. It’s exhausting in a good way!

His NIAf legacy is a film he began developing while there and is still working on. At First Sight is a simple enough idea (a man and a woman each racing a car toward the other and slamming on the brakes just before the collision) but he promises the story “starts getting really crazy” when they embark on a stand-off in the middle-of-nowhere location of the film. Wonder what the storyboard for this one looks like?

Anton Setola’s film Jazzed (2008) was actually completed after he left NIAf in May 2005. But it capped a large amount of experimentation and two other shorter films Mirror, Mirror (2005) and Out Of Sight (2005) whilst there. His was a last minute, accidental application – to say the least. “I stumbled upon some fellow animators in a bar”, he recalls.

“One of them was attending the NIAf and he told me about it. Time was so short to apply that I took a train to Tilburg and delivered it in person just in time. It was a place where I did all the things I should have done when I was studying animation in Ghent”, he continues. “I really feel lucky to have had a chance to really experiment at a more mature age and follow my interests without having to worry about the financial aspect.”

Looking back, Setola has some thoughts about the demise of NIAf, in particular the critique that centres on its unwillingness or inability to find a connection between auteur animators and the realities of preparing creative people for the commercial imperatives of making a living from their craft.

“I believe it was becoming a real hub for animation professionals in The Netherlands”, he suggests. “It needed more time to really become the ‘go to’ place, but it was well on its way. The connection between the professional world of animation and students of animation was invaluable. We got to meet and pick the brains of Paul Driessen, Wendy Tilby and Amanda Forbes, Michael Dudok De Wit, and a lot of others. We had assistance and advice from all kinds of professionals in their field. Animators, screen writers, sound engineers, directors, weird people, basically everything we could ask for.”

NIAf, perhaps to its political and, ultimately, existential detriment, at a time of rising nationalism, determinedly threw open its doors to international participants. They often brought with them different priorities, cultures and ways of doing things. Among the last of these was the American/Japanese filmmaking duo Max Porter and Ru Kuwahata and their film Between Times which was also one of the last NIAf films made.

Kuwahata loved everything about her NIAf experience and seems to have had little problem adapting to life in Tilburg after having lived in New York City.

“We had moved from NYC, where it’s fast, busy, overcrowded and chaotic, to Tilburg, where it’s cozy, quiet, and charming”, she says. “I quickly fell in love with Tilburg and The Netherlands but it took a while to adjust to the sense of time. In Tilburg, time felt slower. There was more calmness and softness in the air. Once I got used to the pace of life, I started to experience my art-making differently. Tilburg was located conveniently. With all the bike paths across the country, I had access to everything from Asian grocery stores and Tilburg University where we learned the language, to art supply stores. Travelling by trains, Amsterdam is 1.5 hours, Brussels is 2 hours and Paris is 3 hours away. It was a perfect combination of having a quiet location to make art and having access to all the major cities.”

In NIAf she found a validation for her life as an animating artist in a way that eluded her in the United States. “In the US, I am often asked by people (both artist and non-artist) why are you making short films that make no money?” she starts.

“I struggled to answer this question and kept wondering if there is any sustainability to this life. NIAf was a place that appreciated animation as art and felt that it was an important part of the culture. It allowed artists to expand their concepts, craft and technique. There was an emphasis on education and support for young artists. If this type of structure didn’t exist, how can you expect to have great artists in the future? Now that NIAF is gone, there aren’t many artist-in-residencies that focus on animation. Most of them are short in duration or do not offer stipends. When you’re financially constrained, it becomes difficult to take risks creatively. I hope in the future, there will be more places where artists are given the time, space and financial support to create innovative new work.”

Another participant, Jaspar Kuipers, perhaps comes closest to summing up what made NIAf such a special place to live, work and study in. He completed a piece of installation animation at NIAf called Tracing and began development of a film entitled Finity Calling, which is still in production.

“The main value I think lies in combining multiple values in one institution”, he begins. “There was great value individually in the library, ateliers, and master classes for example, but it was in coordinating and combining these functions together that was the real strength of NIAf. It was a central place that sort of looked out for the Dutch animation sector as a whole and all its facets. It did education, flew in professionals from all over the world to share their knowledge and so on. Because there was direct contact between the people running these departments and the participants, students from art schools and animation professionals, a big network of knowledge was in place that could be tapped into. Now all that is splintered. The NIAf played a role in promoting Dutch animation worldwide and was a voice that was (sometimes) heard by the government. The sector now lacks a common voice. That could become problematic I think, but it is a bit too early to say.”

Leevi Lehtinen is a Finnish animator who resided in Slovakia at the time he applied for his NIAf residency. His film (Ego) (2011) is one of the more unusual and darker films to have been completed there, taking almost two and a half years full time to finish. He makes another salient point about what made NIAf special and unique. “The NIAf residencies were so long lasting. I don’t know any other residencies that are as long. Two years, that was extendable in my case, was long enough to finish a crazy, non-commercial, low budget, overly time-consuming film. We had a one-week master class about four times a year. Additionally, every few weeks we were visited by directors, dramaturges, script doctors etc. Each visitor also gave one-to-one advice on every participant’s project. The library was pretty extensive, but as more than half of the books were in Dutch, it was more useful for Dutch participants. (I’m a Finn.) The film library was great though. Many rare animations that are not available on Youtube.”

Oerd Van Cuijlenborg has realised some of the most accomplished abstract, direct-to-film animations created in recent times. A filmmaker with an astounding natural sense of timing, his films are almost visual depictions of sound in three dimensions. He approached NIAf for guidance when he graduated from art school and was happy to embrace a diversion into animation as a way of escaping the commercial art world he was otherwise heading for; a world in which he felt he would be forever having to defend his work. Like virtually all the NIAf alumni, he credits the unique luxuries provided by the NIAf experience as being something he felt incredibly privileged to have experienced.

“NIAf was really my second chance after art school to properly appreciate having the time to do art”, he says. “The non-curriculum was not for everyone but it was great for me. I took everything I possibly could from it.” Pushed on whether he feels NIAf could have been saved, he is a little more blunt than most of the others interviewed for this article. He wonders out loud if NIAf was evolving; evolving quickly enough or evolving in the right directions to suit a changing culture, shifting political demands and a need to integrate more with the commercial animation ‘industry’.

“I believe there could have been better communication between the participants and the leadership”, he says. “But Ton was overloaded and focused on fund-raising. “However, the government was determined to make these cuts and I don’t think anything could have saved it. Culture is always the first thing to go, which is counter-productive because culture makes people happy and the economy gets better when people are happy.”

Generally, the view that NIAf could not have been saved no matter what they had done is one that seems to be universally shared. Some take it with a resigned shrug, such as Ru Kuwahata.

“I often wonder if it would have helped save NIAf if the participants had been pressured to work to pre-determined deadlines, but I think that would have gone against the goals of the community. Besides, the government wouldn’t have cared less if more films were produced or more awards were won.”

Others such as Anton Setola accept the inevitable whilst still trying to hold on to some sort of optimism. “The NIAf went down because of a lack of financial resources. The arts are vulnerable in that way, so I don’t think it could have been saved. But I do believe it will be back somewhere in the future in some new incarnation, when resources are again plentiful. It won’t be called the NIAf, but perhaps it will be inspired by it.”

And other participants such as Jasper Kuipers see it as part of a more destructive agenda. “I’m afraid that it was inevitable. There were big cut backs in the arts that were part of a politics of symbolism. This might seem extreme but if you ask me the arts were demonised to create a common enemy for the sitting politicians to generate votes with. The arguments they used in the debate had nothing to do with reality so it was very hard to have a debate at all. How can you counter fantasy arguments that sound so much clearer than actual reality to a layman? The body put into place by the government for advising on the cultural cut backs gave very positive advice on the NIAf. This advice was ignored completely by the same government, which to me signifies a different agenda and total arrogance.”

These sorts of cuts and the changes they often force upon established cultural institutions are nothing new, of course, and are not by any means confined to The Netherlands. But they do seem to have been unleashed with a particularly jovial ferocity by the current Dutch government. This wrecking ball has been as swift as it has been broad and it has not played favourites.

The race is on to ensure that these works, the institutions that made them possible, the people that created them and the reasons they were created are not entirely lost. This retrospective is one tiny contribution to the effort to showcase what an astonishing, precious and unique contribution NIAf made to the world of auteur animation – the concept that animation could be practiced and considered as an artform.

Perhaps a Twenty-first Century iteration of a rejuvenated NIAf will emerge, fully formed and relevant to the impulses, technologies and challenges of the current times. We shall see. In the mean time, a good man named Ton Crone continues to work on a number of projects that relate to the winding up of the NIAf we used to have. He is doing all he can to ensure that the NIAf archive is catalogued properly and stored in such a way as to be as obvious and as available as possible for those who follow. Negotiations with The EYE Institute to try and ensure the individual filmmakers retain some rights to their films have been protracted and are ongoing.

The lingering impression, as he heads for the door, is that the wind-up of NIAf – at least for Ton Crone – is more a slow, fading sunset than a sudden switching off of the lights.

NIAf ‘Artists In Residence’

- Christa Moesker (The Netherlands, 1993)

- Jim Boekbinder (USA, 1993)

- Janetta A3AnA (The Netherlands, 1993)

- Liesbeth Worm (The Netherlands, 1994)

- Sjaak Meilink (The Netherlands, 1994)

- Violet Belzer (The Netherlands, 1995)

- Chris de Deugd (The Netherlands, 1996)

- Alies Westerveld (The Netherlands, 1996)

- Marret Jansen (The Netherlands, 1997)

- Mark van der Maarel (The Netherlands, 1997)

- Oerd van Cuijlenborg (The Netherlands, 1998)

- Demian Geerlings (The Netherlands, 1998)

- Jeroen Hoekstra (The Netherlands, 1999)

- Geertjan Tillmans (The Netherlands, 1999)

- Efi m Perlis (Belgium, 2000)

- Pieter Engels (Belgium, 2000)

- Pascal Vermeersch (Belgium, 2000)

- Vincent Leloux (The Netherlands, 2000)

- Danny de Vent (Belgium, 2001)

- Mic Bijl (The Netherlands, 2001)

- Frodo Kuipers (The Netherlands, 2003)

- Mirjam Broekema (The Netherlands, 2003)

- Terry Chocolaad (The Netherlands, 2003)

- Anton Setola (Belgium, 2003)

- Valentijn Visch (The Netherlands, 2003)

- Uri Kranot (Israel, 2003)

- Michal Pfeffer (Israel, 2004)

- Anneke de Graaf (The Netherlands, 2004)

- Raymond van Es (The Netherlands, 2004)

- Maik Hagens (The Netherlands, 2005)

- Paulien Bekker (The Netherlands, 2005)

- Marta Abad Blay (Spain, 2005)

- Dirk Verschure (The Netherlands, 2007)

- Coen Huisman (The Netherlands, 2007)

- Maarten de With (The Netherlands, 2007)

- Niek Castricum (The Netherlands, 2007)

- Joost Bakker (The Netherlands, 2007)

- Leevi Lehtinen (Finland, 2007)

- Annika Uppendahl (Germany, 2008)

- Kris Genijn (Belgium, 2008)

- Anne Breymann (Germany, 2009)

- Maarten Isaäk de Heer (The Netherlands, 2009)

- Sjaak Rood (The Netherlands, 2009)

- Arjan Boeve (The Netherlands, 2009)

- Evelien Lohbeck (The Netherlands, 2010)

- Jasper Kuipers (The Netherlands, 2010)

- Frauke Striegnitz (Germany, 2010)

- Digna van der Put (The Netherlands, 2011)

- Max Porter (USA, 2011)

- Ru Kuwahata (Japan, 2011)

Malcolm Turner, MIAF Director