On Oct 30, 21:00 at the Barbican, we’ll be screening a 3D Stereoscopic programme curated by the National Film Board of Canada (NFB)‘s Head of 3D Animation, Munro Ferguson and introduced here by Malcolm Turner (LIAF Co-Director & Director of Melbourne International Animation Festival – MIAF)

Find out more or book tickets here

The NFB has been experimenting with 3D stereoscopic animation longer than almost anybody. Their earliest experiments date back to the 1950s when the legendary Norman McLaren created Around And Around and Now Is The Time in full 3D stereoscopic on 35mm film. A more recent incarnation of these experiments is the creation of the NFB’s Stereo Lab unit. Part production studio, part pure research and development facility, touring it is a fascinating and often unpredictable experience. It’s not uncommon to walk around a corner straight into the middle of a darkened room that seems to have dancing white lines snaking through thin air towards you or a giant fish apparently slithering up a wall.

Ever the pioneers, the NFB has also created a lot of their own software and devices to further their understanding of what this particular form of cinema can be pushed to do. At the core of most of their work is a system called SANDDE (short for Stereoscopic Animation Drawing Device) that was developed in conjunction with IMAX. It is an utterly amazing technology to behold, allowing artists (and the occasional ham-fisted visiting festival director) to hand draw 3D stereoscopic animation and see the results (in full 3D) in real time before their very eyes. Standing in a dark room, holding a fancy pen in your hand, moving it around in a rising corkscrew fashion and then standing in front of a two-metre tall three-dimensional corkscrew that appears to be hovering above the ground a couple of metres from your face is… just magic!

Head of the NFB Stereo Lab, Munro Ferguson, knows this technology better than probably anybody else. Munro has been instrumental in the development of SANDDE and other 3D stereoscopic animating systems within the NFB. In earlier days, he worked on this with Roman Kroiter, one of the original founders of the IMAX film format, who passed away in 2012.

Munro chose the films in this programme. He has, at one level or another, been involved in each film’s development and production – and done a great job. It seems a bit presumptuous to tell somebody like Munro what to do so I gave him free rein to choose whatever he felt should go into the programme – except I may have let slip that I really wanted Moon Man. The main fact you need to know as you watch Moon Man is that a ‘Newfie’ is a person from Newfoundland, the chilly, sparsely populated most eastern extremity of Canada inhabited by a hardy, pragmatic people who speak with something approaching their own dialect and who either learn to live within the environmental constraints of their land or perish. This film comes complete with a contagiously simple sing-song soundtrack.

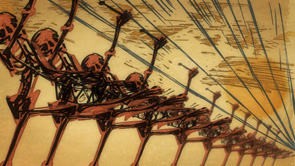

An extraordinarily special element of the programme is the fact that we will get to see not just the final and latest film in Theodore Ushev’s trilogy of 3D stereoscopic works, but the entire trio, back to back in all their glory. Theodore is Bulgarian born but lives and works predominantly in Canada. His latest film, Gloria Victoria, was all but finished when I last saw him in his studio at the NFB bunker in Montreal last September. The soundtrack was still rough then and he was only able to show me what he had on his computer but I knew it was special at a glance. The opportunity to see the trilogy together is a special treat and this will be one of the first times it has happened. The first film of the trilogy, Tower Bawher (2005), is a “whirlwind tour of Russian constructivist art celebrating the genius of constructivist artists, while also offering a scathing commentary on art in the service of ideology”. Ushev made this in about a month and while its native format is 2D, its translation to 3D stereoscopic has produced a runaway freight train of a film with an audacious visuality.

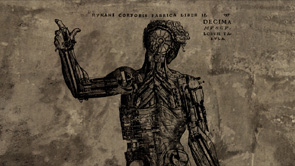

The second film, Drux Flux (2008), picks up where the first left off introducing a rolling, post-industrial, apocalyptical, photographic montage into the visual mix, driving home the point that the theme of this work is set in a very real, frighteningly identifiable world rather than simply in a more dismissible imagined abstract space. His latest film, Gloria Victoria, blends these two environments, recycling elements of cubism and surrealism and focusing on the relationship between art and war, leading us from Dresden to Guernica and from the Spanish Civil War to Star Wars.

This programme is where the promise of 3D stereoscopic comes together. It may change but right now creating 3D stereoscopic animation is expensive and is a technologically fraught exercise for anybody who does not possess the right equipment. This doesn’t just work to withhold it from the hands of the vast majority of auteur filmmakers who might want to work in the 3D stereoscopic space, but it closes out anybody who might wish to develop a project anywhere other than one of the relatively few, highly resourced organisations, which, by and large, are organisations that have a narrow view of its value and need to get it to dance on its hind legs to pay for its supper.

The National Film Board of Canada breaks that paradigm. Return on investment is measured differently there. And it has the equipment. It is a place where auteur filmmakers and artists have a fighting chance of receiving the support and resourcing they need to achieve their creative visions. There is A LOT to be said for that and this programme is the best chance we will have of seeing just what 3D stereoscopic can do when the deadweight of commercial imperatives is cut loose.

Malcolm Turner

Thanks to the Quebec Government Office, London.