Couldn’t quite shake the feeling that we hadn’t finished dancing with the ‘real’ in the intro back at Programme #2 (Playing with Emotion) so let’s pick up that thread again here. Alternative explanation for this opening paragraph is that the introductions were written out of sequence this year and what should have been a direct follow-on ran into the problem that the intros for programmes 3 and 4 had already been written and subjected to the festival director’s penetrating eye.

Whatever the real story, we left out (or shied away from) any mention of Walt Disney and his complicated relationship with reality (at least in his cartoons). A lot of people tend to assume that us animation festival types probably don’t like Disney films or at least won’t admit to doing so.

Nope, Disney created some of the most wonderful animation ever made and set benchmarks that will likely never be surpassed. And Walt Disney himself was, in so many ways, one of the first people to truly believe in the latent potential of animation as a form worthy of striving to reach perfection in. In chasing that exact dream he went bankrupt once and, after he’d picked himself up from that experience, lost control of the first genuine character he created (Oswald The Lucky Rabbit) when he went to his backer to ask for an increase in film funding so that he could make the films better. His backer, the odious Charles Mintz, responded to this proposition by reducing the funding and threatened to take Disney’s Oswald character off him if he couldn’t make the films for the new, lower price. Disney was astonished when his entire staff of animators (except his great friend Ub Iwerks) deserted him and went to work for Mintz. Disney vowed never to give up the rights to a character ever again, but that’s another story.

The point is that Disney was putting himself through this purely because he knew his cartoons could be better if he was given the chance to prove it; he had a faith in the uniqueness and power of animation that almost nobody else had, at least almost nobody else in the United States.

In his excellent book ‘Of Mice And Magic: A History of American Animated Cartoons’, Leonard Maltin quotes Disney as saying:

“The cartoon business didn’t seem to be going anywhere except in circles. The pictures were kicked out in a hurry and made to price. Money was the only object. Cartoons had become the shabby Cinderella of the picture industry. They were thrown in for nothing as a bonus to exhibitors buying features. I resented that. Some of the possibilities in the cartoon medium had begun to dawn on me. And at the same time we saw that the medium was dying. You could feel rigor mortis setting in. I could feel it in myself. Yet with more money and time, I felt we could make better pictures and shake ourselves out of the rut”.

At the same time, Disney was becoming more and more fixated on the idea that animated films had to have a basis in reality. Sure, mice can’t actually play guitars (at least not in any lab the cameras have been allowed into) and ducks aren’t famous for live-long commitments to their nephews but Disney had an instinct for how to blend the magical and the real. And while his sense of where that boundary was drawn differed from film to film, his commitment to this style of animating only became more ingrained as he got better and better at making it. As Amid Amidi outlines in his beautifully produced book ‘Cartoon Modern’, Disney animation became “firmly entrenched in nineteenth century pictorial realism with the aim of creating an ‘illusion of life.’”

“As the studio’s films began to feature increasingly nuanced character animation and realistically rendered backgrounds, they also began to look more like live action; the fantastic worlds that the studio created in its early features … were always rooted in “a foundation of fact,” per Walt Disney’s orders, and the drive for realism often trumped the graphic possibilities inherent in the art form.”

But Disney never wavered – and why should he have. His films were loved the world over by succeeding generations and he was really good at making them.

The sheer weight of Disney’s dominance of the animation scene saw the slavish connection to this ‘animated realism’ push the artform of animation in a number of different directions not the least of which was the rise and rise of minimalist animation made famous by the cartoons produced at UPA: Gerald McBoing-Boing and Mister Magoo being but the most famous standard bearers.

But the issue of how to use animation to depict something that has a grounding – somewhere, somehow – in reality is one of the most exquisite challenges animation throws up, regardless of the age it is created in or the technology it is created with. Make it ‘too real’ and the film falls into the category of orthodox animation outlined in the Programme 2 introduction. Take it too far the other way and it might wind up making no sense whatsoever – not that there isn’t the odd spot in the line-up for one or two of those.

How the ‘real’ is depicted is all the more important when you are making the kind of films that find their natural home in a programme like this one – Looking For Answers. As often as not, they are the kind of films that are striving perhaps more than some others to offer a more foundational sense of the ‘real’ while at the same time using all the unique properties of animation to explore that very basis in particularly interesting and unusual ways.

The programme kicks off on pretty solid ground. Return by Marcos Sanchez actually uses real live-action footage of days past and memories captured as a platform upon which to add a lot of heartfelt, handmade animation. At its core, this is a spoken word poem performed by the Botswana born, Netherlands based poet Supermoon Blues set to music. It talks about life lessons learned and what could be passed back to the younger self if only that were possible to do. The live-action footage sets the tone for the reality of the younger times the older self remembers living in but it is the animation that superimposes onto that the possibilities that only hard won knowledge and experience can offer. It is a beautiful mix of two different realities blended together to create a very large whole – a real reality lived in the past and an imagined reality suite of how things could be – if only. The unpredictable part is will anybody seeing it now absorb the wisdom of ages and bring that into their young life? It’s possible, which makes it worth a try.

In a lot of everyday situations there’s nothing more real than nothing. “What did you do at work today?” “Nothing.” “What did you learn at school today?” “Nothing.” It can sometimes be hard to pin down the minutiae of everyday living, especially when nothing is (the) normal. Somebody transported into our daily commute from 500 years ago would have a lot to report back. Beyond the repetitive nature of a lot of what fills our world, we have also lost the impulse to notice and even celebrate the little things. Nature, even when jammed in hard against the materials of a city, seems like a dependable source of wonder if we want to turn our eyes to that. The mystery of a half heard conversation or the often press-ganged randomness of the colour palette that confronts us at every turn might bring a little extra tint and shade to a passing view. Iizuna Fair by Japanese artist and animator Sumito Sakakibara is nothing but this – and more. Its original format is that of a 360° ‘animated painting’ commissioned and displayed at the Nagano Art Museum in central Japan. That experience must have been a sight to behold and translating it to the cinematic version screening in this programme was done by presenting it as one long, continuous slow pan across a panorama of always moving action. There is no discernible narrative and although there is a lot of little real stuff happening the temptation is to say it’s about “nothing”. But maybe it’s about life, which isn’t exactly nothing. Look for the details, the minutiae, the thing that’s just a little bit out of place here and there or behaving not quite the way it should. It’s a delicate balance of animated reality and odd moments that only animation can produce.

Viewed through this type of prism, the films in the programme progress quickly through an incredible array of differing ‘realities’; and they display the endless possibilities open to animators to use the artform to find that balance between the phantastical and the real.

Slow Light by Katarzyna Kijek and Przemysław Adamski takes yet another tack. The ‘real’ in this film is a completely ingenious narrative construct around the notion of delayed time and the animation is put to work immediately to reinforce that. This it does right out of the blocks in striking style, bringing to screen a particularly bold and vivid iteration of cut-out stop-motion animation that even manages to display a couple of new technique twists here and there.

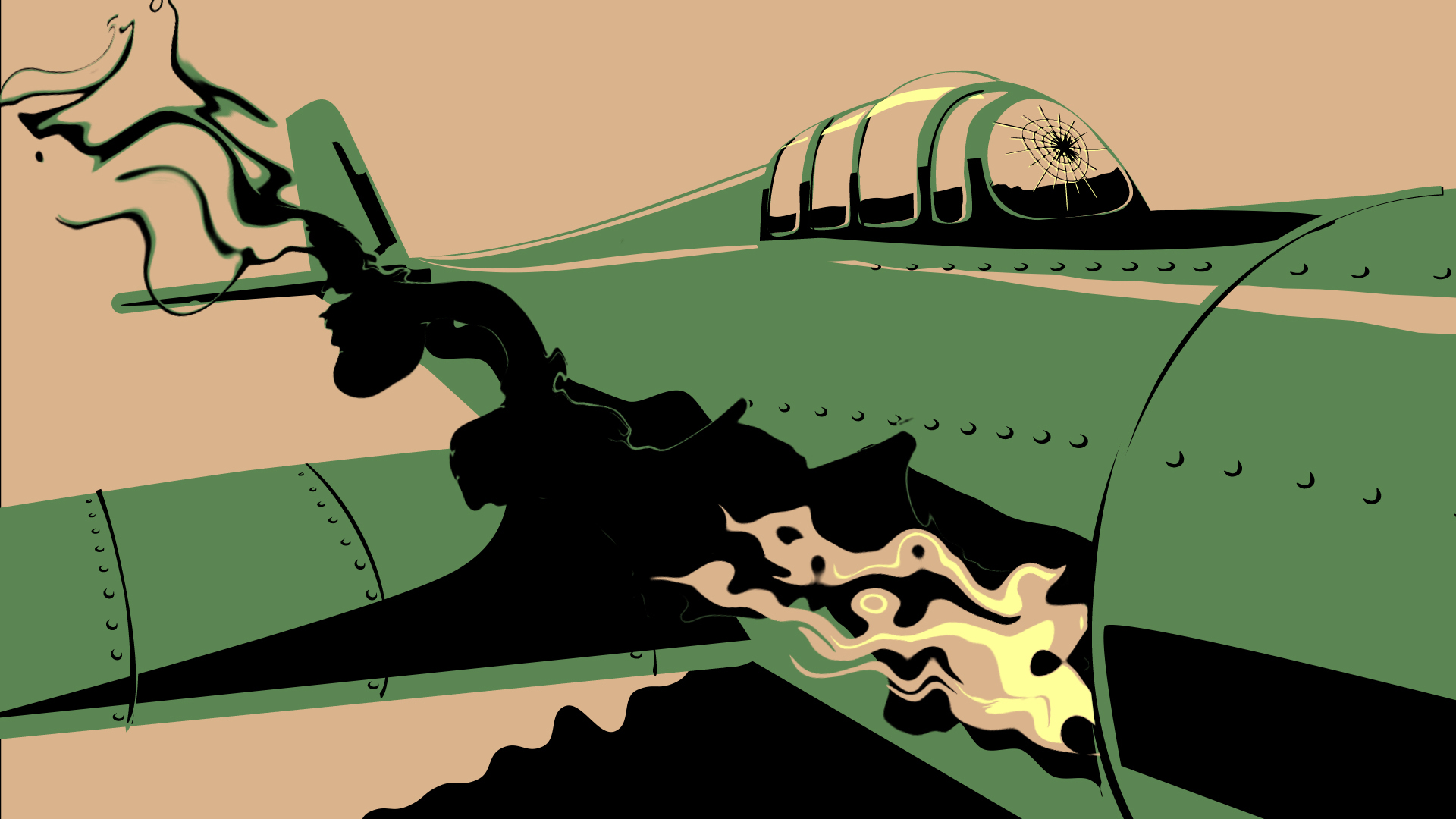

It works in almost the opposite direction with Andrzej Jobczyk’s Airborne which uses an astonishingly creative ballet of animated ideas to virtually deconstruct one of the grimmest realities mankind knows and transform it into a work of pictorial beauty and a celebration of pure imagination.

And Of Wood by Owen Klatte uses a giant block of wood as its canvas. If this has been done before we haven’t seen it and yet – at heart – it’s such a simple and captivatingly clever idea that it’s a wonder it hasn’t been tried. To make it work one needs the skills of a carver which Klatte obviously has in abundance but the blend of natural material and the sense of textural connection that this work relentlessly renders before our very eyes frame after frame has to be experienced to be believed.

The programme finishes with the much awaited, much anticipated new film by Canadian master animating duo Amanda Forbis and Wendy Tilby. The Flying Sailor is by any measure a bravura turn. It is based on a true story; that of an early 20th century sailor by the name of Charlie Mayers who, while standing on a shipping dock in Halifax, Canada, took the full brunt of a massive explosion that occurred when a ship full of TNT went kaboom. In more recent times, many of us will have seen the extraordinary footage of the massive blast that rocked the Beirut port in mid 2020. Imagine getting caught in that. Forbis and Tilby – somehow – have created a virtuoso piece of abstract animation that offers the closest impression any of us would want to have of what that would look like or how our minds would capture it as a visual interpretation of the experience of being in the very centre of that maelstrom. It’s a compelling and visceral visualisation of something that probably cannot really actually be depicted; an imagined iteration of a hyper-real moment. What follows is the immediate aftermath of that moment of manically-kinetic madness and in all likelihood the film lasts longer than what it depicts but if it ran in real time we would never get to see the beauty inherent in it, nor at least the drawn, imagined reality of what that moment looked like. And what of seaman Mayers? He was thrown two kilometres by the blast and survived. And that’s unreal!!!

by Malcom Turner

Looking for Answers screens at The Garden Cinema Wed 30 Nov find out more