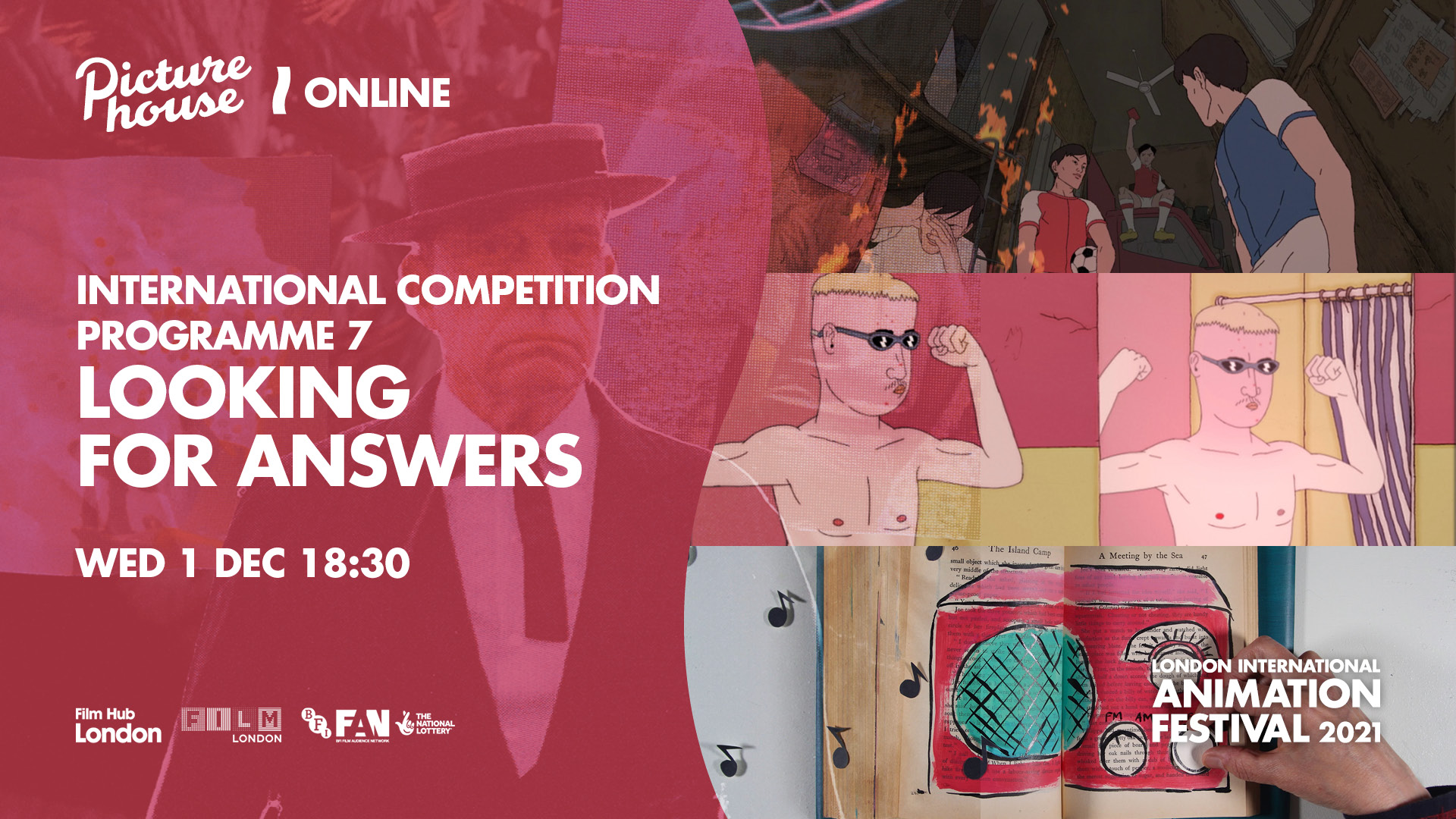

At Hackney Picturehouse book tickets

ONLINE: book tickets or buy a pass

The similarities between animation and poetry are as obvious as they are under-recognised. An animated film has vastly more in common with a poem than it does with a live-action short film or a piece of short prose.

Think about it. How many films do you see in LIAF that simply offer up a three-act, beginning-middle-and-end structure? Introduce the characters and story, introduce tension, increase tension, resolve the tension, tie up all the loose narrative threads, credits. Not many.

Sure, you caaaaaan do that in animation but what a waste of the astonishing potential of animation to bring other, different and more creative layers and nuances to a film. It’s like using the best oil paints to paint your house.

Even better, the audience expectation(s) for what an animated film should be and could be go well beyond the relatively simple, finite perimeters of the general expectation of a live-action film viewer. Likewise, a quick flick through the pages of the Guardian to touch base with how swimmingly all things governmental are going should be straightforward to read, to the point and at least somebody’s version of a defensible subjective reality. Small indeed would be the readership which would want a summing up of the current roster of wars, political misdeeds and business shipwrecks in a voice that aspired to be channelling Yeats. Horses for courses.

Poets, on the other hand, illuminate the invisible, describe the inexplicable and offer us a pathway that expands how we might view and interpret all that we encounter in the world. They are able to do this not because they are smarter than a journalist but because they have licence to use language any way they choose. They are the chef who constructs a meal on the fly from a miscellany of ingredients and a sense of how these harmonies can be unified versus a cook who labours over a recipe and knows they will be judged on how close they get to the goal that recipe proscribes.

Are there ‘no boundaries’ to what an animator is ‘allowed’ to do? That would be a bold claim. Even the universe as we know it has a hard wall out there somewhere. (Perhaps Kafka has already designed and staffed the door in it that nobody is brave enough to go through.) But the animator – as the poet with language – can chase and create the more dissipated aerosol of an idea in a way the poor buggers stuck working the literalist side of the street can’t get their bosses to sign off on.

It’s a privilege to be given a mind that works this way.

Just off The Bowery in New York there is a wonderful, relatively modest gallery named the Tibor de Nagy Gallery. Perhaps counter-intuitively, given its name, it focuses almost exclusively on showcasing contemporary American artists. Its point of difference – either by design, chance or evolution – is that it has also served as something of a gathering place for American poets. Inevitably, wonderful fusions abound.

A favourite is the montage collection they hold of upstate New Yorker poet and artist John Ashbery. His long-form poetry is, at its best, nothing short of a provocative, impassioned ‘Call To Thought’ for anybody with the right set of ears. Interestingly, a lot of his montage pieces include characters from famous comic strips and cartoons.

Writing in The Yale Review recently, Edward Hirsch summed up the critical mass of Ashberry’s work:

“Ashbery’s poems establish a pattern of opening up and closing down, of disclosure and concealment. They reveal, they re-veil. They embrace what he calls ‘the charity of the hard moments,’ they welcome and embrace change. They are flow charts that repeatedly push back the locking into place that is ‘death itself.’ This is the reason that Ashbery can be so rewarding and frustrating at the same time. He is a poet of perpetual deferrals.”

Reveal and re-veil. Perpetual deferrals. Striving to challenge rather than clarify. Demanding that the reader interpret rather than consume.

All these things and more are the bedrock of what the unique properties of animation can bring to our search when we go ‘Looking For Answers’.

This synthesis of poetry and animation infuses the delicate lattice of the opening film in this programme How To Be At Home, a collaboration between poet Tanya Davis and animator Andrea Dorfman. To some degree it is the stepping stone closest to shore of a journey that explores this ‘raison d’animation’ in increasingly complex detail as the programme progresses.

Commissioned by the National Film Board of Canada, it picks up where an earlier viral hit collaboration, the 2010 ‘video poem’ How To Be Alone left off. The myriad uncertainties that the newly arrived Covid might impose were an added ingredient that gave this new work a shade the original never had.

This powerful combination of words and images is more a harmonisation than a synchronisation, in as much as both words and images, although often matching, each carry broader and more interpretive powers unique to their individual artforms.

A similar turmoil of tangled emotionality and interpersonal misalignment simmers all through Trona Pinnacles, the latest film by Mathilde Parquet who is rapidly establishing herself as a significant new voice in French animation as she moves forward from a raft of awarded films she created whilst studying first at EMCA and then La Poudriere.

Anybody who has found themselves bound into a slowly disintegrating family structure will recognise all the cues evident in this complex portrait of a situation that words cannot adequately describe – in part because words and language have passed their ‘use-by’ date here. All that is left in the space are gestures, the dirty flood wash of emotional ebb and flow tides and the latent potentiality of imminent implosion.

In a strange, fascinating, almost Dadaist kind of way Co-Ognition by Przemyslaw Swida explores exactly the same sort of potential for emotional disintegration via an entirely visual rabbit hole. This is the search for and portrayal of meaning within a deliberate language and narrative vacuum. To that extent it’s a natural, if not more ephemeral, progression of the pathway the first two films in the programme has set us on.

The animated philosophy of Yuanqing Cai, one of the co-directors of Coffin somehow combines elements of each of the films that preceded it and, at the same time, reinforces one of the key points from which we started.

“I feel copying from reality is not the best choice in 2D animation,” he said at the Clermont-Ferrand festival earlier this year. “You capture these images and copy them from your mind; you are not a machine copying from reality.”

“We don’t want any big story, I think it’s a trap,” he added. “We only have a few minutes and we want to focus on emotions and on the characters.”

Canadian animator Mike Maryniuk was the subject of a retrospective screening at this year’s Ottawa International Animation Festival. Maryniuk would have to go down as one of the more overlooked independent animators. Entirely self-taught, his work has a rough-hewn, ripped-edge aesthetic to it and his films often possess a structure that many find hard to grasp as they rush by. The OIAF screening should help lift his profile a little and the fact that his latest film June Night was produced at the National Film Board of Canada brings a polish to his work that elevates the resolution without sanding out the cut-marks of his craftsmanship.

June Night is a montage waterfall, a veritable deluge that spools past us with an intensity that perhaps masks the intention behind the image selection thought process and the role each moment might be playing in supporting and countering those in the flow. Whatever a viewer takes from this, Maryniuk’s apparent fixation with Buster Keaton notwithstanding, probably has as much to do with how they absorb this visual scrabble board of images being constantly tossed into the air before their eyes.

Cradle by Paul Muresan walks us back a little from that ledge, dropping us into a more readily definable space, albeit a darker and more emotionally challenged one. Muresan is happy (or at least willing) to admit to an obsession with drawing.

“For me drawing was mesmerizing,” he said in an interview with filmsinframe.com late last year. “I just thought it was amazing that you could take a white piece of something like paper and create a world out of it. Bring out an emotion in another person. This idea totally fascinated me.”

Just as well. Cradle took nearly 9,000 individual drawings to create.

Muresan has also thought a lot about how the history of animation has influenced the kinds of films he strives to make. Realising early that the earliest animated films were riven through with coded imagery designed to skirt censorship regimes and that Disney created multiple generations of animated fans that were being primed to equate beauty with heroines and ugliness with villains, Muresan has developed a practice that prioritises the kind of hard honesty that he thinks reflects the complexities of the way we experience life’s challenges. Cradle has a keener narrative edge to it than any of his previous films but, ultimately, it poses more questions than it answers.

LIAF has always loved Gina Kamentsky’s films. There would not be many years we have not screened at least one of them and, of course, in 2019 we had the pleasure of welcoming her as a judge. LIAF regulars will recall a collection of films that in many cases draw from and build upon the ‘direct-to-film’ technique, in as many cases as not involving abstract or abstract-ish imagery imposed upon found footage live-action photography.

Not as well known within the animation community is Kamentsky’s art practices in montage and sculptures created from repurposed objects. We humbly suggest a visit to her website for a primer. Her latest film Soft And White is imbued with elements of this thread of her creativity. It is captivating and migrates a texture, dimension and visual depth of field from her sculptor’s studio into her animation. It will be fascinating to see if this is a rare treat or a new direction!

There have been reams written about dreams. They’re curious components of the filmic world; sometimes deployed as either the laziest of all segues, overhanging platforms for a plunge into terror or uncertain canvases upon which to tease out misshapen and intriguing alternative realities. Real Life by Rosalie Loncin quickly comes up to speed, dragging us into a twisty and supple version of the latter. Nominally we – and the protagonist – leave the dream behind. Maybe so, but not its blurred and mystifying logic. It’s a clever clash of conscious dimensions and mirrors the convoluted, discordant ways our brains sift through available evidence in pursuit of an elusive meaning.

It will become apparent fairly early in the piece why we’re not the only festival programmers that didn’t want to decline Anna Samo’s new film Conversations With A Whale – it’s a strategy surprisingly few people use …. thankfully!

This is a wonderful example of what is known as under camera animation – which is a technique requiring the artist to draw the scene she wants to depict on a bench top, photograph that and then draw over or rub out whatever sections of the picture she wants to animate; photograph that and repeat that process over and over – usually 12 frames for every second of animation. This often produces a lovely ‘ghosting’ effect which gives the film a unique life and vibrancy and this is definitely evident in Conversations With A Whale. But Samo takes the technique a step further here, sometimes using elements of collage and physical materials (such as sand) to bring yet another dimension to the finished work. We were more than happy NOT to have rejected this film.

One last lurch to poetry as we head towards the apogee of ‘Looking For Answers’. English writer J.A. Baker is best known (if he is remembered in this day and age at all) for his masterpiece work ‘The Peregrine’. Released in 1967, it is a beautifully realised amalgam of creative pose and the DNA of poetry. Werner Herzog compared it to the work of Conrad and said it is the “one book I would ask you to read if you want to make films.” If one rummages around BBC Radio 4’s website long enough an audio version of it read by Sir David Attenborough will make itself available at some point.

In her new film Peregrine Daniela Sherer takes six defining lines from that book and uses them as springboard into a world crafted in the kind of bold elegance that she does so well. The fact this film comes at us in an uncompromising jet black and bright white colour palette only enhances the power and force of what is on screen while at the same time paying due respect to the emotional undercurrents that flow through the book.

And we have saved arguably the most literal (and strangest) looking-for-answers film for last. Easter Eggs by Belgium animator Nicolas Keppens comes at us with a much heftier payload than his hilarious graduate film “Wildebeest”. It’s possible to extract a thread of humour from some of the veins of “Easter Eggs” but there is an acidic base-spirit to this cocktail that you might want to protect your skin from.

The whole thing comes from a place that is simultaneously dramatic to those caught in its vortex and just another near-invisible blip on the radar of life for those not living in the same neighbourhood.

“When I was a kid, the baker in my grandmother’s street committed suicide,” Keppens recalls. “He hung himself in his aviary with beautiful parrots. He left the door of the aviary open and all his colourful birds flew away. In the days following the death of this man, my older friend and I looked in the gardens around my grandmother’s house to see if we could find these birds. This was the starting point to tell something about the age we change rather fast from a child into an adolescent. Games become reality, we want to be taken seriously, but no one does.”

The imperative to search for the loose threads of meaning in the tapestry of life’s random, uncontrollable events is the engine under the hood here though with whip-sharp dialogue and the dangerous frisson of the lead character standing in as the fuel that brings the machine to life.

Malcolm Turner – LIAF Co-Director