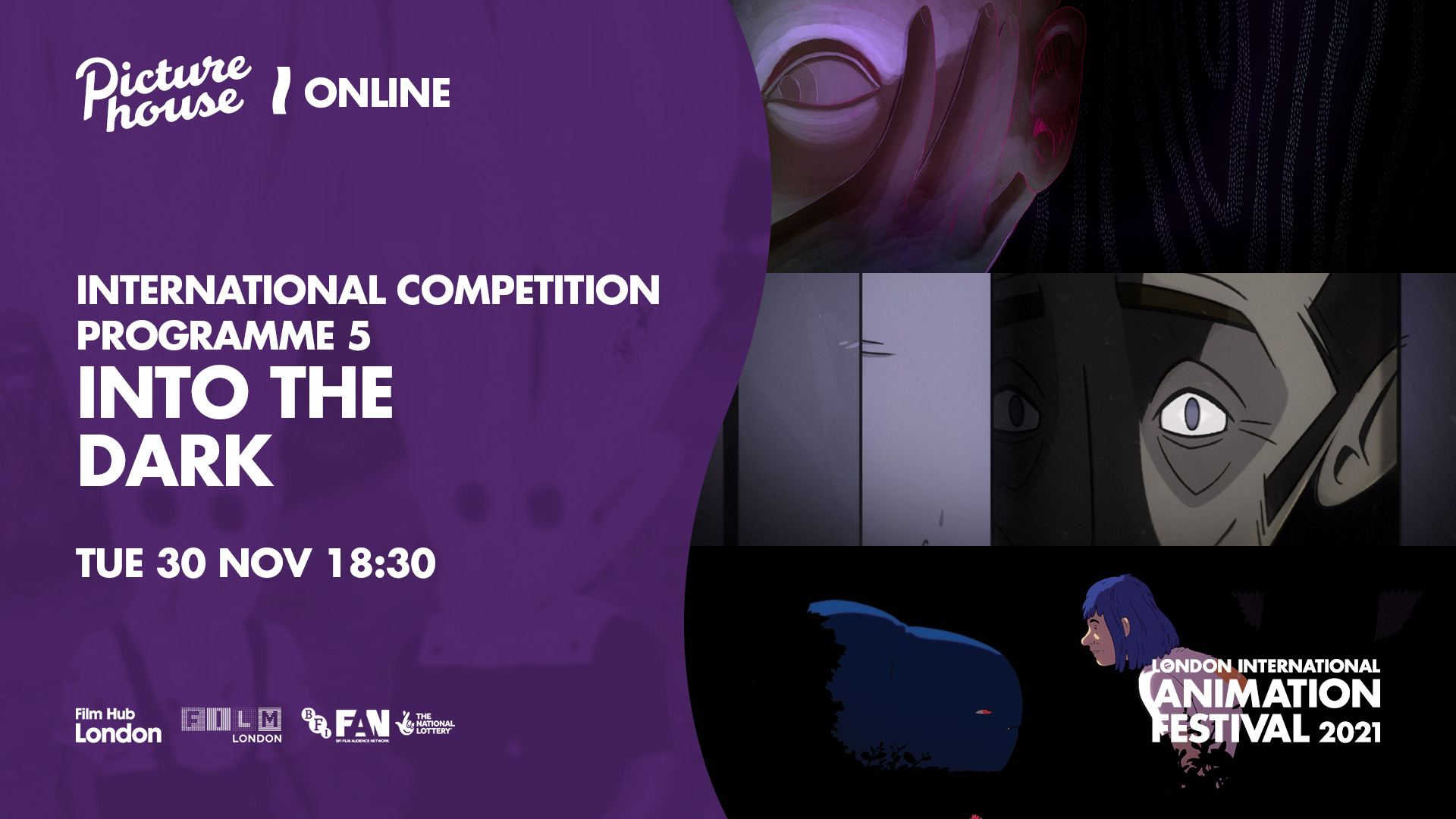

At Hackney Picturehouse book tickets

ONLINE: book tickets or buy a pass

Even for us this is a bit of a stretch – at least at first glimpse. But this odd stepping off point for ‘Into The Dark’ kind of appeared out of the light so let’s see where this takes us. If you’re reading this then this idea is still alive.

“The man who most truly can be accounted brave is he who best knows the meaning of what is sweet in life and of what is terrible, and then goes out undeterred to meet what is to come.”

Pericles (rhymes with John Cleese)

In other words … he’s looking ‘Into The Dark’. It’s an interesting quote that speaks to the complexities of contemplating the darker side of the human condition rather than the simpler, more raw-gut reaction to the fears, failings and fragilities that we all know lurk large and small in both the real world we wander in and the inner world we carry around with us.

In truth we’re not big Greek history scholars here at LIAF HQ but it’s a quote that popped up in another context around the same time and it resonated. It did so, in part, because the core message in introducing our ‘Into The Dark’ programme is to move those ‘first impression’ reactions away from the simpler (and sometimes more vivid) raw-gut assumptions and attempt to provoke a deeper reading of much that is contained in the viscera of these films. And, as always, it’s the potential of animation that brings that unique dimension to what these films present and to interrogating the assumptions and extended realities that underpin them.

Statesman, warrior and cultural leader, Pericles spent more than his fair share of time looking ‘Into The Dark’. But, for him, it was a dark containing plenty of colour. He fought wars only when he was certain emotion played no role in raising arms. He’d seen anger fuel a rush to the battlefield and, as often as not, result in catastrophe. Pericles wasn’t a fan of catastrophe. As a wildly popular politician he was nonetheless forced from office by betrayal of friend and foe alike (his own son denounced him) but he fought back to win a stunning election little more than a year later. And he saw the construction of a powerful and empowered social culture as the best defence to restrain those who sought to impose their murkier will on the masses.

It can be a curious place, the human dark heart. Easily misinterpreted as a malignant asset, it can in fact project any colour and, sitting as it does in the middle of us all, it radiates out in every which way.

Mood is the essential ingredient of a number of this year’s ‘Into The Dark’ films. Mood settles across Steakhouse like smog, blurring the vision and threatening to choke the central characters caught in the compressed anger that inhabits the world they must know is broken. Its director, Spela Cadez, is a master at creating this all-enveloping atmosphere. We were lucky enough to visit her studio in Ljubljana in late 2019 as she was getting production underway.

Steakhouse has the same pastel malevolence as her previous film Nighthawk, an effect that pits her exquisite hand drawn artwork and her quirky sense of lighting against the hazy effect of (literally) the lid of a pasta dish through which most of the action is shot. The effect is almost claustrophobic and serves to seriously blur the edges of the action. This has the effect of simultaneously hinting at what might be lurking at the edges and concentrating on the subtle, rising horrors of what is happening centre screen. And one can only wonder at the feelings of the vegetarian crew who found themselves working on this film.

Mood, too, is a central and visceral brine which soaks into all the cracks in Dad Is Gone, Pere Ginard’s new film. Officially montage, it is more akin to a pulsating scrapbook of x-rayed nightmares. Festivalscope.com describes Ginard’s practice as “the exploration of perpetual motion and the melancholic creation of ghosts, monsters, prodigies and mystical outbursts”, which touches on the mood of the film but barely begins to describe the terra-macabre that animates the horror-army of still images as if they were gripping the bare ends of electrical wires.

Bouncing into a world of subterranean narrative, Ghost Dogs (Joe Cappa), Cut It Out (Inez Kristina) and Something In The Garden (Marcos Sanchez) each in their own way lean into the dark impulse that so much great animation has in utilising creatures as conduits for exploring fears, the lashing out of ill-defined angers and as stand-ins for human characters expressing proto-human emotional corollaries. This stuff can range from the shock of the unexpected through to the uninvited portrayals of phobias grounded in the loss of one’s mind or body in a world in which both are the only essentials that really matter. Animation has an entire tool kit purposely created to deliver these sorts of velvet jolts directly into the psycho-plexus because so often the very properties of animation act as a kind of perceptual local anaesthetic lowering the resistance at the point of entry.

The best animators instinctively understand that ‘time’ is a critical element in an animator’s arsenal. Time not so much as a measurement tool but more as an actual ingredient in their creative process in exactly the same way as they would think of paint, puppets or digital outputs.

Hide by Daniel Grey is a great example of this. Time is a BENDY ingredient in this film – not just something that is used to keep track of the story or the protagonist’s progress. Daniel somehow stretches the sense of time being experienced by the little boy like a baker stretches dough and as it stretches over one axis or another, it affects and alters the version of reality that the film is projecting at any given moment. It’s a transnational effort. Daniel is a Welshman who lives and works in Hungary. The film draws on funding from Belgium, France and Canada, is co-produced by the National Film Board of Canada and distributed by our friends at Bonobo which is based in Zagreb in Croatia.

There can be no more practised, refined and well trodden pathway for going ‘Into The Dark’ than the seemingly unquenchable human passion for war. The shape of war has changed over the years as have the gadgets, the tactics, the motivations and, to some extent, the prizes. But some things have maintained a kind of dependably depressing constancy to them. People in the way of rolling militias are rarely spared and there seems to be an enduring gene in some people who levitate towards profiting from the misery of war, apparently capable of extracting riches from those who have nothing.

Clara With A Mustache by the Kosovar director Ilor Blakcori takes us into the middle of this horror with an almost audacious precision. In some ways it’s not a unique story but the way Blakcori has marshalled the potential within animation brings angles and illuminations to the many personal dimensions of that story that could not be portrayed in any other medium.

The title speaks to the first character in the film, the face on the 100 German deutsche mark bill. This was the currency of choice in Kosovo before the Euro arrived and on that banknote was the portrait of Clara Schulman, one of Germany’s most renowned pianists and composers. Her music, not surprisingly, permeates the film.

It’s a personal story too…. a very personal story. It reflects the experiences of many of the people who worked on the film and their memories of the dark days of war in Kosovo, a war which is thankfully over but which cast tentacles that still hold much of the rubble within their grasp.

And what (you ask) became of Pericles? In the end he died in a pandemic that swept through Athens in 429BC. All things old are new again – never underestimate the potential for history to repeat.

Malcolm Turner – LIAF Co-Director