Do you or anybody you know suffer from xylophobia? Perhaps you are more familiar with its slightly Anglicised name, hylophobia? No? Interesting, because a lot of people suffer from an irrational fear of forests and wooded areas. That being said, some level of at least heightened concern about forests is a reasonably rationale attitude. If the experts are to be believed, this particular phobia is comprised of a number of contributing factors including a fear of animals, a fear of being lost, a fear of the dark, a fear of abandonment and, presumably, nomophobia, otherwise known as a fear of not being able to access your mobile phone.

Forests are – rationally – scary places. They just are. Beyond the real, mortal risks that they offer, they can also rapidly become very foreign environments full of a gradually metastasising gloom that slowly seeps into our deeper fears and corrodes our faith in our own certainty of place and our reign of personal autonomy – both physical and mental. A forests’ capacity to instil fear and dread is in some ways more sinister than so many other hostile environments. If you sail off on the ocean, climb up a mountain or wander off into a desert you have a pretty good idea what you are up against. But a forest? You can have a picnic in the forest.

Tell that to Little Red Riding Hood, Hansel and/or Gretel or half the other characters that the Brothers Grimm created outright or curated from the mists of oral folklore during their time. Interesting, too, is how many of Edgar Allan Poe’s tales and poems wind up being set in a forest when they are translated into film. On the page, not that many of them are so situated but there is something insidiously, compellingly ‘foresty’ about their aura that in so many cases the filmmakers cannot resist the temptation it seems.

The connection, perhaps, is that what Poe does so well and so often is to wholly and compellingly capture a sense of loss of personal autonomy over the self and the senses that, by its nature, is a key ingredient to xylophobia. “You fancy me mad,” writes Poe in perhaps his most famous of all stories, ‘The Tell Tale Heart’.

“Madmen know nothing. But you should have seen me. You should have seen how wisely I proceeded – with what caution – with what foresight – with what dissimulation I went to work!”

He then goes on to kill an old man for no other reason than an aversion to one of his eyes.

It is a concise index to the steep, steady descent into inexplicable madness; the incremental loss of mental autonomy; a blown gasket letting viscous sanity leak out until the mind is running on empty. Peerless, perhaps, until the arrival of ‘The Clockwork Orange’.

It is little surprise, then, that most of the films in this year’s ‘Into The Dark’ programme have one or both of these themes kneaded into their core. Tenant (Sarah Benson) brings into shrieking focus the notion of the silent scream and the caustic psychic erasure of lives lived in quiet desperation. The visceral, textural magnificence of Noctuelle (Martin A. Petrlicek) brings a more tactile feel to a similar sense of inner foreboding and films such as Polka-Dot Boy (Sarina Nihei) and Mekakure (Akifumi Nonaka) go out of their way to explore that arresting fear of being taken over from the inside out as if by an alien or body snatcher.

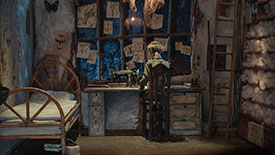

Pandora (Matthias Lerch) stalks a similar quarry, but in reverse. It is meta-film in a sense, taking over the very machinery of filmmaking to make a film about filmmaking. Old timers will more readily recognise the mechanical detritus Lerch re-purposes here to construct an alternative reality and, piece by piece, a menacing character perfectly attuned to that environment. The carnivale-grotesque that assembles before us shows no signs of being satisfied with being sublimated as mere actors and props relegated to a future offering nothing more than the promise of a suspect immortality as a stored image awaiting projection: this stuff wants to live.

But the programme starts as it means to continue and ‘Into The Dark’ at LIAF 2020 is in large measure a long and winding journey through a collection of forests. 100,000 Acres of Pine by British animator Jennifer Alice Wright was completed at The Animation Workshop in Denmark. She packs a lot into its seven short minutes. There is a narrative scaffold that gets the story going and introduces us to the characters but quickly the forest takes over – and as it does the mind of the protagonist begins to falter. 100,000 Acres of Pine rapidly and superbly marshals all the underlying potential of the forest to become the lead character and as it emerges as a presence in its own right it proceeds to set an agenda more in synch with its power to channel the residues of all the dark myths that forest mythology insinuates. How much is really happening to Megan and how much is playing as a lived nightmare drawing energy from the suggestive powers of what the darkest forests are capable of harbouring is hard to know but it is a gauntly drawn co-production of the best that Poe and xylophobia can muster when they are forced to share the production credits.

Forests are presumably more welcoming habitats for animals, even if the evidence doesn’t necessarily bear that out for lots of the littler, more edible members of the broader menagerie. Still, it’s hard not to feel some hope for a couple of the animal inmates that star in Algen (Erik Svetoft) when they pull off a zoo-break after a particularly bad day trying to entertain the human attendees. It does not take long for a bigger, more saturated picture to emerge. Animals do some pretty heavy narrative lifting in animation and this duo has a heftier burden than most.

Algen is a colourful cluster-bomb of observations, warnings and unresolved ledgers. Humans have weaponised their power over animals and there is a shield that we have stretched widely but incredibly thinly between them and us to help us recalculate the one-sided, dangerously abusive nature of that relationship. Hand in hand with that is the leaden progress we are making in understanding how the environment ‘they’ live in is being affected. We seem stalled as spectators because it is hard to admit we are anything but.

Wild Beasts by Marta Prokopova and Michal Blask has a very different cadence to it. The forest is more background hum than anything and the hybridity of the human/animal characters constantly contorts, staying just out of our grasp. Highly atmospheric, it interweaves three stories skilfully laying a breadcrumb trail that allows an audience to trace back to a place where a more whole construction of the characters could be made. In Wild Beasts the forest feeds into the overall atmosphere almost by osmosis but it’s a quietly pulsing life force providing just enough background power to keep the lights on.

This sparingly interconnected little treatise on our attitudes to forests and the ways they are treated in animation holds together with a certain serial clarity …. until Stephen Irwin turns up. Imagine a character who is a cross between BigFoot and a paint truck explosion and is chasing the son of a cousin of the lead character from Gremlins (set to Grieg’s Peer Gynt) and maybe you have some sort of introduction to his latest film Wood Child And Hidden Forest Mother. Then again…..

Irwin’s charming weirdness has always been a top-shelf treat for the part of the psyche that loves this all natural sugar hit. Even by Irwin’s standards though, this post-language beauty defies any attempt at lucid summary and sane categorisation. The dark cosmology that infuses the film with its essential joie de vivre is an explosively perfect counterpoint and counterpunch for the raucous lunacy that it erupts.

‘Coming Into The Dark’ is one thing but we couldn’t resist sending you out into the light.

ONLINE Pre-order tickets

Malcolm Turner, LIAF Co-Director