Eccentric. Screwball. Inexplicable. Unreal. Curious. One-of-a-kind. Intriguing. Bizarre. Twisted. If you put Atsushi Wada into the Thesaurus, these are the results. We LOVE his films. They have a look and style all of their own but they come with their own unique inner rationality that is Wada’s and Wada’s alone.

Eccentric. Screwball. Inexplicable. Unreal. Curious. One-of-a-kind. Intriguing. Bizarre. Twisted. If you put Atsushi Wada into the Thesaurus, these are the results. We LOVE his films. They have a look and style all of their own but they come with their own unique inner rationality that is Wada’s and Wada’s alone.

Kicking off a programme with his latest film, My Exercise, was just irresistible. And in this strange age of lockdowns, lock-ins and ‘do-everything-at-home’, it is a film that brings a comical haze to an otherwise grey reality. It is a film of simple ingredients…. boy, dog, Wada’s imagination. Stir. Let settle. Repeat.

And perhaps oddly for a programme entitled ‘Being Human’, there are a lot of films offering an animal cast. Animal characters are, of course, one of the largest animation tropes there is. They span all genres and types of animation and have done so more or less from the earliest days of animating. Over the years animators have learned how to utilise them to craft messages, construct souls and stitch together storylines that find a different conduit – and deliver a different impact – into the consciousness of the audience than would be the case if straight narrative, live-action filmmaking attempted it.

One of the most quietly powerful examples of this is Mascot by South Korea’s Leeha Kim. What ultimately gets under the skin here is not just the subtlety and the pitch-perfect pathos that radiates out from the sweetly sad centre of the lead character but the unique take the film offers on the animal stand-ins that populate its dimly colourful, oddly askew little universe.

Kim’s film is hardly the first film (animated or otherwise) to delve into the world of animal mascots but somehow he has found a slightly different angle on the whole emotionality of his subject. It’s not so much a ‘through-the-looking-glass’ type of film but feels more akin to looking at a reflection of a reflection of a reflection – real, sometimes very simply so, but somehow back-to-front some of the time. And whoever did the narration gets an A+.

Flipping that lens, A Family That Steals Dogs by John C. Kelly deploys animals as animals to explore a kind of delicate psychopathy at the heart of the collective human cast of the film. It gets harder and harder to know what to trust or believe as the journey descends into what often appears to be dark rabbit holes of the mind and the wobbly memory of the narrator. The animals here may well be silent and powerless witnesses to the story but also serve as sounding boards for a roster of fears and insecurities that we all – if we are being honest – share to some extent. It may be simply a matter of Being Human.

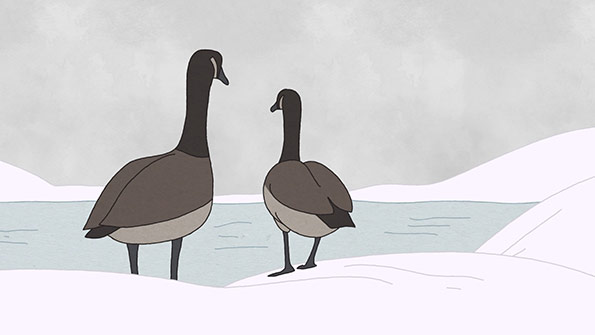

We all remember Captain Sully skimming that powerless jet onto the Hudson River a few years back and everybody getting off with wet feet and most of their cabin bags. Viewed around the world as something of a cross between a miracle and an act of brilliant airmanship, it probably did not resonate as happily for members of the avian community. The story of the geese that got sucked into those engines did not have the same happy ending and Hudson Geese by Bernardo Britto approaches the story from that angle. In doing so, it serves as a reminder that compassion for others is a reaction we do not always have on auto-pilot.

The film that probably blurs the line between animals and humans the most in this programme is Carrousel by Jasmin Elsen, a Belgium/Czech co-production. It is set in a sparse and bizarre theme(less) park containing an imaginative menagerie of cast members that oscillates seamlessly between the bewildering and the downright inexplicable. This motley bunch undulates through a strange, perpetual communal ballet, ever ready, willing and able to turn on each other at anytime as part of an endless cycle of shape-shifting.

“The devil sees you no matter what you do” is an unusual song to issue forth from a child’s lips – even if that child is represented as a small bird, nonchalantly holding a parent-bird’s hand as they gaze at a zoo exhibit. This is how Something To Remember by Niki Lindroth von Bahr opens. Her last film, the astonishing The Burden was judged Best Of The Festival here at LIAF in 2017.

In Something To Remember we have those other-worldly sets and the almost meta-human animal characters that we recognise so readily from The Burden and that commandeer our attention, but we are being taken into a more shadowed inner world this time around. Suturing together the collection of micro-scenes that make up this film is an elusive, post-melodic anthem of angst, cataloguing a range of simple human moments that – added up – seems to be saying “this is how it is; this is what it is”.

The point at which this programme pivots from animals to children is best represented in Deux Oiseaux by French animator Antoine Robert. It’s hard to make a definitive judgement about the lead character, a small boy, more or less alone, in a world filled with animals he is still building relationships with. The fanciful, almost innocent cruelty that children are capable of is probably something most humans are born with a capacity for, but hopefully grow out of – in large measure through a gradually rising reservoir of empathy borne out of painfully won personal experience. But the wiring that manages this mental software is complex and flimsy, and fails to upgrade automatically in some cases. Motivation and intent can also temper pure malevolence. You just never really know what’s ticking over in those little minds but here Robert skilfully takes us into the complex world of an evolving value system that makes sense primarily (or only) to its owner.

This window into the young human perspective also sits at the centre of Lia Bertel’s film And Yet We Are Not Superheroes. However good a medium animation might be to create films for children, it is a superb, almost custom-made platform for exploring the modulating dimensions of how children see the world.

There can be a lot of strange connections being made in those little still growing, still learning, still developing synapses. Then again, strange is in the eye of the beholder. And, hey, think about it – before too many rules get pushed in, dulling the brightest lustre on the outside of the imagination, many a kid’s logic stream can be the most honest and the most ‘sensible’ of the lot, unhindered as it so far is by the abrasive friction of the rationality of the real world. It is precisely this free-flowing river of alternative reason that empowers every transition, every leap and every curve through which this film travels.

It is quite a trick and proves the power of animation to journey outside of the streams that can only float standard narratives upon them. It is a reminder, too, that imagination is one of the key attributes that separates us from the characters in a David Attenborough production. Being human is an interesting position to find oneself in. The ability to overlook and to forget seems to be part of the privilege we claim for ourselves as part of the package but one of the roles of art is to remind us that we create a liability when we do that. Every artform has its best artifices for performing this function and this programme showcases some of animation’s most affecting and effective avatars.

The live action guys say never work with children or animals. It’s a whole different ballgame down in Animation Land.

ONLINE Pre-order tickets

Malcolm Turner, LIAF Co-Director