LIAF has always loved abstract animation. Showcasing this kind of work was one of the reasons we started the festival in the first place. But back in 2008 when we actually first took the plunge and dedicated an entire International Competition programme to abstract animation we did not quite realise just how much the LIAF audience loved it as well. The response was immediate and it was clear that abstract animation had found a little toe-hold in these shaky isles.

LIAF has always loved abstract animation. Showcasing this kind of work was one of the reasons we started the festival in the first place. But back in 2008 when we actually first took the plunge and dedicated an entire International Competition programme to abstract animation we did not quite realise just how much the LIAF audience loved it as well. The response was immediate and it was clear that abstract animation had found a little toe-hold in these shaky isles.

Elevating the Abstract Showcase up the order into pole position as the first of the International Competition Programmes, likewise, was simultaneously a bold and obvious thing to do. It is an annual refrain but within the world of independent animation, abstract films are a substantial proportion of all the work being produced; some years it can exceed 25% of submissions, depending on how one defines ‘abstract’.

Making it and watching it is an outstanding way to free the mind and engage with the edges of the imagination. Pure imagery.

It is perhaps not so surprising that the website of the Academy of American Poets is actually titled Pure Imagery. In many ways poets and abstract animators have a lot more in common with each other than they do with colleagues who use the same tools to craft outpourings of more definitive natures.

The LIAF Abstract Showcase this year continues the mission. It reunites us with some of the contemporary masters of the form, brings us up to date with some rising stars who are beginning to build a body of work and develop their own voice and, perhaps most encouraging of all, it harnesses a cluster of films that reinforce the fact that abstract animation continues to have its ranks swelled and re-charged by first time and student filmmakers. That these animators see the creation of abstract animation as the best use of their time, talent and creativity says as much about the potency and power of abstract animation as a compellingly expressive artform as the fact that there are people who can demonstrate a career in making it.

The programme starts with a film for the age we are living through. Irina Rubina’s Black Snot And Golden Squares is a treasure, born in part out of her reaction to the pandemic. Somewhere down in the middle of it is a paean to the value and power of close connection with people, and what it feels like to have that suddenly closed off. But Rubina lists a coterie of inspirations that range all the way back to the gorgeous geometrical ingenuity of Oskar Fischinger and the softened, balletic swirls of Walter Ruttmann, bringing the same colour-pop and jazz timing to her film that she wove through her student film, Jazz Orgie (2015).

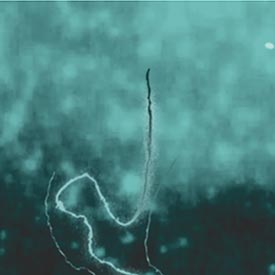

The influences behind Jon Dunleavy’s Everything Is Going To Be OK veer decidedly more Eastern. Dunleavy channelled the Japanese philosophy of ‘Wabi-Sabi’, a word whose meaning sits somewhere in the intersection of undefinable, untranslatable and rejecting perfection.

“I used this philosophy to drive many aspects of the project, including a central visual and narrative beat of a tree momentarily blooming before being destroyed, and narratively, the film plays with an imperfect balance of the central ‘character’ being removed from the narrative just over halfway through,”

he tells Stash Magazine.

It is an approach he applied to the filmmaking process itself and, through it, he has produced a piece of astonishing stream of consciousness that is more a journey than a film.

Firefly by Lee Yun is a beautiful visual poem on, well, fireflies. There is a deceptively simple, singularly brilliant idea that fuels this film. Lee essentially photographs watercolour blobs and then sets about transforming these into squadrons of vibrant colour mimicking the kind of orderly chaos that only fireflies probably understand.

“I wanted to make it like a beautiful symphony of patterns, colours and sounds,” he says. “Elements change and transform, being harmonic and yet keeping their characteristics.”

Escape Velocity IV by Zai Tang and Simon Ball sets out in the exact opposite direction. At heart, it wants to emphasise the aural and uses an ever-evolving eddy of imagery designed to make us interrogate the instant, subconscious links we draw between the visual inputs we allow in and the sounds our minds actually register under that influence. It is a continuation of an extraordinary set of animation installations previously crafted by the pair that each, in their own way, explore the savannah of our inner responses to multiple stimuli.

Beauty’s where you find it. Probably nobody knows or understands that better than an abstract animator. Some of them see it as part of the job description to share some of those excavations. British animator Jon Gillie has gone deeper than most on this mission. His two films in this programme, Shinnin Kawaguchi and For Aoki Shukuya, although quite different, both emerged from his fascination with imagery inspired by the innermost workings of the human body. Electing to use Japanese autopsies and early Japanese medical handbooks, Gillies’ films offer us a passage through a vista of intriguing complexities that irregularly undulate between significantly abstracted extractions of the raw creative material and something approaching a comforting representationalism. Totally fascinating.

Elemental also, but in an utterly different way, is (Invade) by Wong Man Sze. This is hands-on, instinctive animating happening before the eyes. Charcoal on paper is a beautifully ethereal way to create abstract animated imagery. Lines seem to all but draw themselves while more condensed blocks of shading seem to grow and shimmer as if almost alive. Although doing primary service as a music video for the Hong Kong instrumental band ‘More Reverb’, (Invade) is a gently palpable reminder of the raw beauty that can sit in the heart of the simplest, most organic of images.

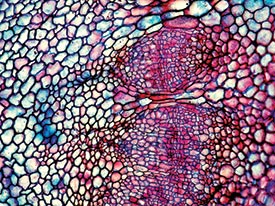

Random Acts, how we love thee! Since 2011 Channel 4 has, through its Random Acts programme, been showcasing groundbreaking examples of ‘moving image’ art. It is not all animation, of course, but it was responsible for helping Michael Hughes’ new film Xylem see the light of day. Xylem is another film in this programme that uses a microscopic excavation of human molecularity as its fuel source. The look and sheer speed of this work belays this inspiration though, blanketing the screen and the senses with swathes of interwoven patterns that could just as easily represent the work of ancient rug-makers as it does that of whoever boiled up our innermost innards.

The variety of techniques employed by animators seems to come from a bottomless handbook of options. Can you imagine what it takes to create a sustained pageant of ever changing, ever morphing outlines out of lengths of thread against a Vaseline coated glass plate? Try and keep that in mind as you watch Natalia Spychala’s film Marbles. Spychala runs a studio in Lodz, Poland, in which she constantly experiments with a wide range of innovative stop-motion techniques and this is the latest offering. It HAS to be an interesting place to visit.

“This has to be the first abstract animation about the economy,” said Ottawa Animation Festival Artistic Director, Chris Robinson, when he introduced Vessela Dantcheva who’s film Hierarchy Glitch screened there earlier this year. Hierarchy Glitch was one of the films that made up the feature length collection entitled Happiness Machine which matched ten female animators with ten female composers. Animating an ever twitching matrix and glossing much of it with a deliberately gilded aura, Dantcheva plots an abstracted tango of markers which strive to hint at the myriad variable behaviours that might be realised in the economic theory known as the ‘Common Good Economy’ model. Luckily, no prior knowledge of advanced economics is required to appreciate Hierarchy Glitch but it would be interesting to know what an actual economist took from it. Sadly, we don’t know any.

We have been showing the work of Oerd Van Cuijlenborg since we started LIAF. Originally from the Netherlands, these days Van Cuijlenborg resides in Paris and his latest film, Winter, was definitely a ‘lockdown’ piece. In fact, it was the original lockdown that gave him the opportunity to finally get to work on this project which he had had in mind for some time. The plan is to complete four films to match the four seasons of the Vivaldi masterpiece. Van Cuijlenborg brings a 21st century flair and sheen to the earlier teachings of Norman McLaren’s cameraless animation and in doing so, gives the tone and style of that technique a contemporary relevance and a platform for the future. Even by Van Cuijlenborg’s standards though, Winter is an incredible piece and as well as being about as pleased as we can be to give it its world premiere, we will be paying close attention to the next three ‘seasons’.

Speaking of the future, if we have animators like Ross Stringer emerging then animation has one! His film Trunk Calls shows a young animator intimidatingly adept at working in a number of techniques to create hybrid films requiring everything from a large stack of blank paper through to a pretty hefty render farm. Recently graduated from UCA Farnham Stringer has been busy, having already directed an earlier film (Mind In Motion) last year and lending animating and co-directing horsepower to some others. He brings a cinematographer’s eye to the composition of this visual essay and you get the sense that, fascinating as this is, he is only just getting going.

Serial Parallels is the latest work by Max Hattler, surely one of the most innovative, acclaimed and screened digital moving-art makers in the world today. Serial Parallels has already screened at close to 100 festivals and shows no sign of letting up. Restless, in a laid back kind of way, Hattler seems capable of endlessly rethinking uses for the tools of his craft. The sheer breadth and volume of the construction of imagery in Serial Parallels is almost too much to contemplate. There are artists who toil with great skill and care to utilise a variant of this technique to create a single, complete photograph. Here Hattler has created thousands (if not tens of thousands) and stitched them together to create a relentless moving montage, seamless and apparently able to move through every axis. Utterly remarkable.

And we send you off into the night (or whenever you get to watch this) with a film guaranteed to lift the spirits and make at least a few of you mutter…. “where do they get their ideas?” The answer to that question for Melinda Kadar, the maker of The Wellspring And The Tower is ‘cosmic anxiety’.

“The larger order of things is not lost just because there is some kind of current environmental destruction going on,” she said recently, when asked to expand on the theme. “The larger equilibrium will be established at some point.”

It is a hopeful take on the way we are grappling (or not) with environmental issues in the here and now and her film brings a captivating, all-enveloping aesthetic to the screen. It is easy to be swept away with the majestic but mellow fullness of it all but the trick Kadar deploys here is to somehow fill the senses without overwhelming them, thus leaving plenty of soft handholds with which to hang onto the core message of the film.

In all, 14 films that are but the tip of an iceberg. Perhaps one of our most diverse Abstract Showcases, this programme highlights the vitality and vibrancy of the abstract animation ecosystem. It is a form with – really – no boundaries and, clearly a committed community of makers providing all the momentum it needs.

ONLINE Pre-order tickets

Malcolm Turner, LIAF Co-Director