International Competition Programme 5: Long Shorts screens at Barbican book tickets

Pulling LIAF together each year is about maths as much as anything else. The average length of all the films submitted for Competition in LIAF this year came in at just under six minutes. And that’s probably about the average length of the films that we wound up selecting. Coincidence? Self-fulfilling prophecy? Hard to say. But as the selection process narrows it can be tempting to favour eliminating a 15 minute film to make way for five 3 minute films. Having a programme dedicated entirely to the longer films has helped us avoid falling into that trap and that was the original impetus for adding Long Shorts to our line-up way back in the day.

Of all the ‘Long Shorts’ we have screened, this particular iteration of the programme probably showcases the widest cross-section of the different ways animators go about making the very best use of all of that extra screen time.

Job Roggeveen, Joris Oprins and Marieke Blaauw met when they were studying at the Design Academy Eindhoven. In 2007 they formed their own studio ‘Job, Joris & Marieke’ and had early success creating award winning music videos and working on some high profile animated TV shows. As successful as their first auteur film Mute (2013) was, it was nothing compared to the profile that the 2014 follow-up A Single Life achieved, taking them all the way to an Academy Award nomination.

Their latest film Heads Together builds on both the visual style and the snappy narrative approach they are rapidly turning into a readily recognisable house-style. At heart, Heads Together relates a pretty simply idea but the real charm of the film is the extent to which we are given the opportunity to get to know and become familiar with each of the characters in the film. Altogether, it’s a very beguiling whole and weaves a simpler, yet more sustained and satisfying, yarn than so many animators who attempt a straight-up narrative film are able to muster.

Impossible Figures And Other Stories II by Polish animator Marta Pajek hails from a very different neighbourhood and speaks with a much different tongue. It sweats a dystopian aura of broken golem, threat and veiled surveillance. Somehow channelling the essence of an unpublished Edgar Allan Poe tale and the most sinister intentions of The Lion, The Witch & The Wardrobe, it is a film that rolls in tightly wound episodes, absolutely epitomising the raw power of animation to make the impossible irrelevant.

A woman tripping and stumbling around a house, soon discovers she is attempting to navigate an edifice made from far more (or less) than wood, bricks and windows. Pajek uses animation to portray the inner workings of her mind, releasing her protagonist into this bizarre environment to try to make her own sense of it in pursuit of a quest that equally quivers with a sense of the nearly impossible.

The artform of animation is awash with filmmakers who understand and try to harness its power to depict the many facets of what the Absurd looks like or means. Although less of a fool’s errand than it might sound on the face of it, nonetheless getting it right is one of the Himalayan-sized grails of animation.

Thomas Nagel is one of the world’s most entertaining and accessible thinkers on the topic of Absurdism. His many articles and books are a window onto the possibly oxymoronic filigree of what makes the Absurd absurd. An uncredited post on reasonandmeaning.com goes to the heart of Nagel’s philosophy on the subject.

“For Nagel the discrepancy between the importance we place on our lives from a subjective point of view, and how gratuitous they appear objectively, is the essence of the absurdity of our lives,”

it reads before directly quoting Nagel for good measure:

“The collision between the seriousness with which we take our lives and the perpetual possibility of regarding everything about which we are serious as arbitrary, or open to doubt.” *

If all of that be so, then Niki Lindroth von Bahr has grasped the holy silverware with both hands. The Burden is a masterclass into the minutiae of existential anxiety. And it’s set to music. Little wonder it is one of the most awarded short animated films of the year.

Zbigniew Czapla’s film Strange Case chases a similar quarry but veers off the road and crashes through a thorny tangle of subconscious brambles in the pursuit. The questions might be similar, the answers could well turn out to be the same but the journey is more jagged and nerve wracking.

This dark pageant of imagery brings an expressive meaning to many of the emotions and psychoses that sit at the pulsing centre of what this film is talking about. In this, Czapla uses images, colours and light in much the same way as a poet utilises words; they are both chasing something greater than the simple sum of the parts, they are pushing the boundaries of meaning that each of these symbols is usually attributed with and attempting to connect words and pictures with abstract ideas and often volatile, maddeningly incomplete emotions. It’s Czapla’s longest film to date and it uses every single second of its screen time to stunning effect.

Michael Cusack is one of Australia’s most accomplished and experienced puppet animators. His Adelaide based production company, Anifex, is one of the biggest and certainly one of the oldest stopmotion facilities in the country, with a history tracking back nearly 40 years.

Creating personal films – when the schedule allows – is a way for Cusack to express the writer and artist within and recharge the creative batteries. His latest film After All is a superbly crafted piece of poignant, animated theatre. Perfectly pitched, droll humour brings a delicate and understated authenticity to a moving tale about a mother and son coming to grips with her approaching death and occasionally – though increasingly frequently – failing mind. Captured flawlessly here is the unspoken truth that the person least affected by a death is quite often the person who will die.

This is puppet animation as practised by a master; proof that we can be drawn into a world created out of fabric, wire, silicon and wool and believe in what we are seeing and experiencing.

If you haven’t heard of Don Hertzfeldt you must be VERY new to animation. The rest of us have been marvelling and uproariously laughing at his films for at least 20 years now. Once you have seen Billy’s Balloon (1998) you can’t un-see it. And that’s nothing compared to what you will encounter when you watch Wisdom Teeth (2010). His last film World Of Tomorrow (2015) brought the house down here at LIAF when we screened it and we wondered if there was any way he could really top that.

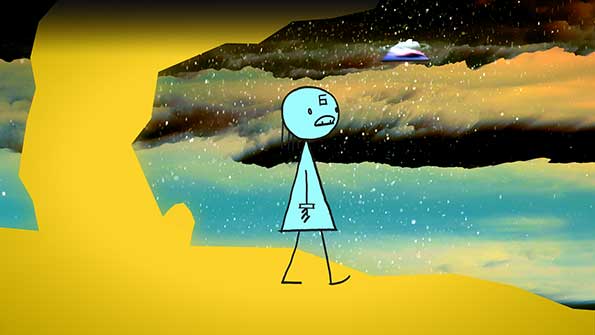

Conceived as an excuse for Hertzfeldt to teach himself the basics of digital animation, written around unscripted recordings of his four-year-old niece, and ultimately nominated for an Oscar, World of Tomorrow is the story of an oblivious little girl named Emily Prime who’s visited by a time-travelling adult clone of herself and spirited away on a whirlwind tour of our species’ mordantly hilarious future.

On the surface, it’s just a disarming pair of stick figures wandering through colourful bursts of jagged computer imagery. One of them talks about falling in love with a moon rock and growing so lonely that she can hear death; the other draws a triangle. And yet, by the time the duo arrives back where they started, their circular adventure through time and space has somehow resolved into an unspeakably profound meditation on the preciousness of the present. “Now is the envy of all of the dead.” What more could there possibly be to say after that?

Blisteringly funny, deeply touching, and endlessly quotable, World of Tomorrow Episode Two: The Burden of Other People’s Thoughts will make you better equipped to live life, and more prepared to accept death. It might only be 22 minutes long, but what more could you possibly want from a long short film?

* ‘Summary of Thomas Nagel’s “The Absurd”‘ find out more

Malcolm Turner, MIAF Director and LIAF Co-Director