An introduction to International Competition Programme 2: Being Human, with extra info about some of the films screening, some trailers and lots of pics!

Being Human screens 6pm, Sun 7 Dec. At Barbican book tickets

Sometimes the simplest things are the hardest to do well. Pixilation is an animation technique that has fooled many an animating hopeful into a cul-de-sac of ill-fated assumptions about how easy it must be to pull off. And while the world is awash with an ocean of stories seeking some new insight into the simple, utterly human anguish of relationship breakdown, most of them are doomed to sink without trace, taking captain and crew down with them. Amelia And Duarte (Alice Guimaraes & Monica Santos) beats the odds on both of these counts – and beats them handsomely.

Packed to the brim with one animating genius moment after another, it is little short of a tour-de-force of the technique. One scene so effortlessly flows into another that it somehow makes this torrent of visuality feel more magic carpet ride than express train. The story, too, builds a surprising depth as it gallops away from the starting gates. It doesn’t take long to grasp that Guimaraes and Santos have given a LOT of thought as to how the unique properties of animation could be harnessed to tip-toe onto some of the riskier, thinner ice of relationship break-up narratives. This is the work of a couple of filmmakers who have thought through every frame, every word and every picture to do some different enough to be different, good enough to be better even throwing in a happy ending drawn from what could otherwise be the saddest of outcomes. It is one of the most ‘complete’ films we are showing this year.

Conflict of a very different kind is the slowly unravelling fibre that flows through the latest film by husband and wife animation team Michelle and Uri Kranot. Canadian and Israeli-born respectively, residing mostly in Denmark and long-term commentators on the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, the Kranot’s pull no punches in portraying this fraying geopolitical scenario as they see it. In earlier films such as God On My Side (2005) and The Heart of Amos Klein (2008), they have brought a graphic reality to this portrayal. More recently, their NFB co-produced Hollowland (2013) took a more nuanced view of the snarled tales that are woven through the lives of migrants and refugees. But here in Black Tape they have chosen to employ a more subtle gaze, simply portraying two protagonists locked in a dance whilst roped together at the ankles. It is a singularly powerful – yet compellingly simple – idea and they let the weight of that idea drive it home.

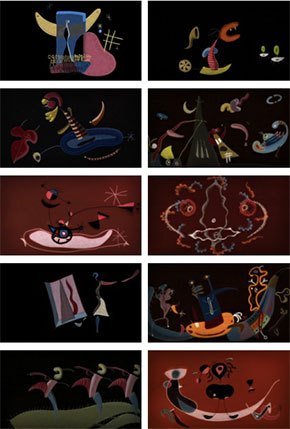

Theodore Ushev needs little introduction to the LIAF audience. He is prolific, able to complete films at an astonishing rate – when he wants to. He is one of only a small handful of animators creating truly unique work in the 3D stereoscopic space and he seems to be able to effortlessly vault from one genre and style to another. Originally Bulgarian, most of his films in recent years have been produced at the National Film Board of Canada’s Montreal studios where his long-term producer, Marc Bertrand, toils in a kind of happy, perpetual struggle to harness all of the Ushev energy. His new film, The Sleepwalker, is a truly independent work though, made with the trademark Ushev rapidity as something of a homage to a favoured gypsy band (not that that stopped him from asking them to change a couple of things to help the imagery of film flow more to his liking).

The pace of Ushev’s filmmaking is – if anything – picking up. Not only is he about to release a new film (animated entirely in blood!!), a recent visit to his NFB producer’s office revealed an incredible second ‘new’ film already completely in the can but copyrighted 2016, simply because they want to let his current films have a little clear air to establish themselves. Ushev himself seems to have little empathy for such strategies. Addressing an audience at the Ottawa International Animation Festival earlier this year, he happily professed to loving releasing a new film and “killing off the last one”. Do we like this new film? Oh yes. Will we be showing it at LIAF next year? Already sorted.

The independent and auteur animation scene in China is still not especially well understood. Social and political barriers exist, to be sure, but they just as surely must be coming down too? Festivals such as LIAF need to do more to navigate those gradually crumbling barriers and find new ways to encourage those films onto screens in the west. Simply posting an open ‘Call-For-Entries’ and waiting to see what turns up is a modus operandi that needs revisiting perhaps. Fortunately a small number of Chinese animators are reaching out towards us and giving enticing glimpses of what must be bubbling away behind those metaphorical walls. One of the most accomplished and interesting of these is Lei Lei. Even as his style rapidly develops and matures, these are still works that simply defy categorisation. Often manically energetic, they possess a core that contains a kind of happily mad rationale even as they discard the comet-dust of looser, lesser formed ideas during their hectic, all too brief trajectory across our screen. His latest film Missing One Player winds the pacing back to about twelve and a half and, at least, lets us get a sense of the situational axis that he is trying to locate the action in. Beyond that however, Lei Lei’s universe still contains much that is apparently left to chance and much that flies in on the wings of surprise, crash-landing on a speckled tarmac of random topography before being shoved out of the frame by the invisible hand and an animator roiling with a need to challenge an audience for every precious second that he knows he has their attention. One cannot help but wonder how these films are received in his homeland.

Stories told in reverse are not especially rare beasts in cinema, theatre and literature more broadly. Nor are stories that require sudden and imaginative shifts in either the physical scenery they are set in or the lives of the characters that populate them. But no artform makes these shifts with such aplomb or with such exquisitely complete ‘differentness’ than does animation. Taking a story, a character and – yes – an audience from a particular place and space to another VERY different one with a seamless elegance is something animation was born to do. Films that make the most of this most unique properties of animation are among the ones that are easiest to select for LIAF. Which is how Edmond (Nina Gantz) made it into the line-up early on in the programming process. Made at the National Film & Television School and stylistically channelling the phenomenally successful Belgium film Oh Willy (Emma De Swaef, Marc James Roels, 2012) it is a rolling masterclass of beautifully imagined, expertly executed animated transitions. These transitions are not just masterfully crafted pieces of animation but also ingeniously woven into the DNA of the story with a wonderfully understated empathy.

This programme closes with a very special film by another NFB based animator, Norwegian born Torill Kove. Although she trained in Canada and has lived there since 1982, she has maintained close links with her homeland. Her 2007 film, The Danish Poet, which took out an Academy Award, was a co-production tapping resources from Mikrofilm AS in Norway and the National Film Board of Canada. Her new film Me And My Moulton repeats and builds on this co-production relationship to great effect.

This programme closes with a very special film by another NFB based animator, Norwegian born Torill Kove. Although she trained in Canada and has lived there since 1982, she has maintained close links with her homeland. Her 2007 film, The Danish Poet, which took out an Academy Award, was a co-production tapping resources from Mikrofilm AS in Norway and the National Film Board of Canada. Her new film Me And My Moulton repeats and builds on this co-production relationship to great effect.

Partly autobiographical, Kove says her film is more about how people choreograph their relationships. Even in the most intimate of relationships she knows that people often give each other presents they don’t really want, such as the surprise 40th birthday party she organised for her husband. Kove also recalls being given a Moulton bike – a distinct type of bicycle created by design genius, Dr Moulton – by her two architect parents when she was a kid and remembers not being sure what to make of it.

“I had never seen a bike like that before”, she told a festival audience last year. “The only other guy in town with a bike like that was the village weirdo”.

It is worth noting that this film was one of the last to be completed by one of the NFB’s most accomplished, enduring and likeable producers, Marcy Page. Page has been responsible for guiding many of the NFB films we have shown here throughout LIAF’s history and for many years before that. She joins her partner Normand Roger (responsible for some of the finest soundtracks ever laid onto animated films) in retirement and this seems an opportune moment for all of us here at LIAF Central to wish them both the very, very best for their future. The Irreplaceables!