LIAF Director – Nag Vladermersky shares his thoughts on this year’s Abstract Showcase programme, which screens today (27 Oct at 16:00, the Barbican). Find out more or book tickets here

What are they spiking Max Hattler’s drinks with? Whether it’s prestigious artist-in-residence gigs in Denmark, delivering masterclasses at Swiss universities and festivals, doing live VJ sets at digital media festivals in Germany or creating high-profile animated light shows on canals in London, (see the film version of it – X – here in this programme), Max is the embodiment of the pan-European digital media artist. Throw in a spot of biennale curation in Brazil, launching commissioned pieces at festivals in Mexico, and delivering programmes of experimental animation in Portland, and you get a picture of a man who must not spend much time at home. X is not the only film of his screening in the programme – we are also proud to present his Animate Projects / Random Acts film for Channel 4 – Shift.

Five films in this programme form something of a ‘technique focus’. Each of them in their own way explores the different ways of directly using physical filmstock. ‘Cameraless’, ‘scratch’ or ‘direct-to-film’ animation is almost as old as film itself. Early pioneers of the technique, such as Len Lye and Norman McLaren, would either use small abrasive tools to ‘scratch’ an image directly on to the strip of film or apply paints, acids and other colourings directly on to the stock. Steven Woloshen is one of the living masters of the technique and his new film When The Sun Turns Into Juice (based on his young daughter’s description of a sunset) is an outstanding example of the purest form of the technique.

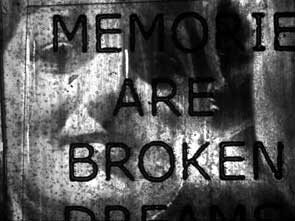

Filmmakers have also enlarged the technique to include re-using old, found, film footage, scratching images into, or painting images directly on top of film that already contains something on it. Typically, the found footage is fairly non-distinct, often even banal – home movie footage, industrial training films, old news footage and the like. Broken Time by Johannes Gierlinger is probably the single most intense and sustained example of this genre I can ever recall seeing. There isn’t a lazy frame in it; every moment is a rich tapestry of painstakingly hand-scratched artwork imposed on top of existing live-action footage with a near flawless sense of balance and juxtapositioning. The rise and rise of digital filmmaking and copying technologies has fuelled a developmental or hybridising process of the technique. With it, the aesthetic of a direct-to-film work can be created and readily blended with entirely different images or manipulated to create an altered version of itself.

To one extent or another, the remaining three films each travel down this path. Dutch filmmaker Oerd Van Cuijlenborg has been making these exact sorts of films for the best part of 15 years. This manipulation of a direct-to-film aesthetic is most evident and obvious in his last film, An Abstract Day (2010), but in his new film, A Direct Film Farewell, it is applied in a more subtle yet complex manner. In some instances, the technique is the main game up on the screen, in other moments, it is integrated with more traditionally animated elements that are transposed directly on top of it, and, in yet other moments, it is frozen as a still-framed backdrop, playing wallpaper to the variously animated foreground components. The genius of this film is not just the revolving uses of the technique but the way in which those transitions are managed so as to be virtually indistinguishable from one another even as they play out before our eyes.

Estonian Ülo Pikkov takes this one step further. The End is, perhaps ‘the end’ of traditional direct-to-film animation; perhaps it is an attempt to draw our eye to the beauty of the unseen, unloved pieces that form ‘the end’ of a roll of film – hell, maybe mixing up the heads (the beginning of a film reel) with the tails (the end of a film reel) is an attempt to somehow have us rethink what an end actually is. This subject is all the more vexing when run through the prism of a discussion on distinctly non-narrative film in which an end of any kind is fraught with endless subjective complexities well beyond “they lived happily ever after”.

Heavy Eyes/Schwere Augen by Siegfried Fruhauf tips its hat to the genre in its opening sequences, gives it a friendly wave as it crosses the street and then, more or less, leaves it behind giving it only passing glances over the shoulder as it skips down the footpath. And yet, as much as this film could have been neither conceived nor made without the existence of computers, neither could it have been made without the fertile backlog of imagery and deceptively simple visual concepts that the earliest form of this technique bestowed upon us. If The End isn’t the end then Schwere Augen is only a beginning.

Nag Vladermersky, LIAF Director

Abstract Showcase screens today (27 Oct at 16:00, the Barbican). Find out more or book tickets here

Pinball / Fliper (Darko Vidackovic) also screens in Abstract Showcase