An Immersion in the Mise-En-Scenery: The Gentle Art of Giving A Frame

We’ve probably had some version of this chat before, but just to recap – and for the sake of those new to the shenanigans – there are a number of reasons for a ‘Long Shorts’ programme. Some have to do with aesthetics, some to do with the pure mechanics of pulling together a festival as large, complex and with as many moving parts as LIAF.

There is always a divine, iron-law pressure bearing down on the structure of LIAF. We don’t select a certain number of films, we curate up to the limit of the screen time we have available to us. There are always (always) more great films than we can squeeze into that accumulated time. And when hard choices have to be made, the blunt mathematics of this diabolical dilemma can easily come to the fore. In other words, saying no to one 20 minute film could allow half a dozen shorter films to play. That is neither fair nor right and locking in one programme overtly dedicated to the longer films helps keep that temptation at bay.

But longer films also often come with a different tone and feel. There’s no definitive mark as to when they have crossed that line, in fact many of them don’t, but you know it when you see it. That can sometimes make them harder to place in a programme with other, shorter films – it can change the entire dynamic of the programme, sometimes compromising the chance for each of the films to shine in their best light.

Longer films will tend to prioritise a flow and degree of storytelling that shorter films can’t manage and so don’t try, focusing instead more on energy and unusual visuality for their impact which, in turn is not always something a longer film can sustain nor a technique the maker of the longer film is interested in pursuing. This ‘difference of tone’ can sometimes unsettle the balance of a programme and how it comes across to the audience.

So while there are a handful of longer films scattered across LIAF’s competition screenings, our ‘Long Shorts’ programme is where we set aside a special stage for them to live their best lives. We are looking for films that make best use of all of those extra screen minutes to do something special with them, to use them for best effect and to do things that simply could not be pulled off in four hectic minutes.

Other than their length, one of the few unifying threads to each of the films in this year’s ‘Long Shorts’ is the incredible way that each director (or teams of directors) have gone about filling their screens. This is hard to do and hard to sustain at the level it is being practiced at here. For want of a better phrase, let’s call it mise-en-scenery.

In theory (OK, in practice too), mise-en-scene is basically how it all comes together. It’s a term we nicked from the theatre crowd but, like love and K-Pop there’s an infinite amount of it to go around so we use it in animation as well. In class after class (after class after class) in animation school, we drill into the students the need to keep mise-en-scene front of mind during every aspect of the filmmaking process, except perhaps other than arranging drinks for the premiere screening (let your instincts run wild for that job).

That is a huge topic but there is limited room here to post a few signposts – plus as soon as I finish this I can start dinner – so let’s refine it down a bit to the slightly smaller field of how the animators have composed the look of their films.

The programme opens with Strange Teen Spirit by French animator, Frank Ternier. Ternier is no stranger to complex, moody narratives whose protagonists drift in and out of varying sub-realities as the story progresses: earlier Ternier films such as 8 Balles, Riot and Quantum Shadow demonstrate that. But with Strange Teen Spirit he has poured on the gas. It is longer than any of those earlier films and more complex narratively and visually. The lead character lives a life riven with doubts and inadequacies and he moves through a world in which the meaning of any given space can change subtly or abruptly with little or no notice. Indeed, the main characters play out their lives skirting laws and norms and endure the consequences of those choices. Ternier has chosen to match that varying narrative structure with artwork that is ever changing. The definition of what constitutes ‘the’ frame in the film is constantly being explored by the maker and interrogated on-screen by the characters. This is a kind of moving montage, giving off an ‘essence –de-framing’ as it travels its course, sometimes helping us to understand what to focus on as we watch, sometimes diverting our gaze and sometimes highlighting the confusion and uncertainty of the characters themselves as they parade before us.

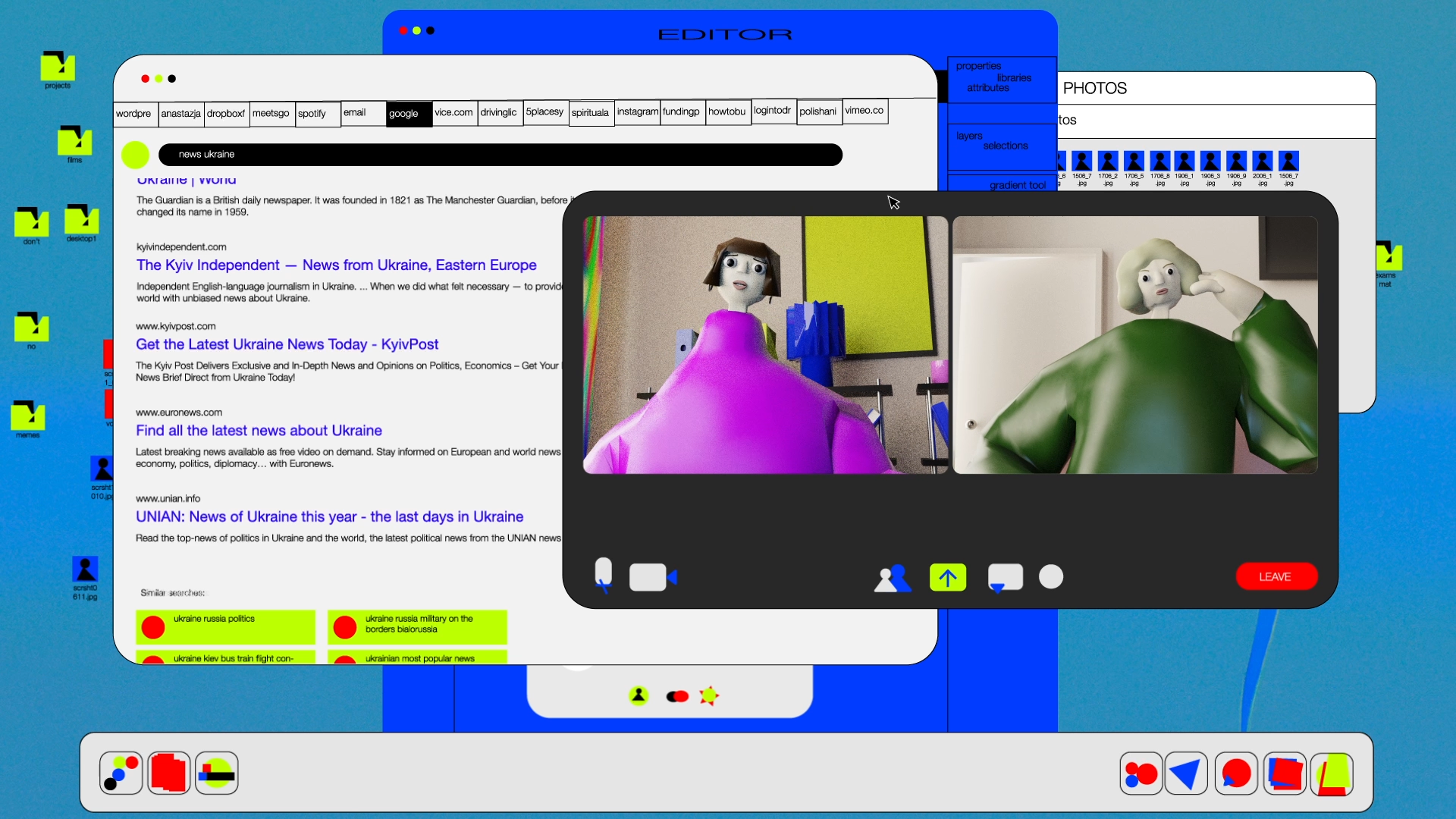

Framing also plays an all-encompassing literal and critical role in the design of Can You Hear Me? by Poland’s Anastazja Naumenko. Here the art is hiding in plain sight, smothered across the screen constructing a pictorial scenario that we probably look at longer than we look at the faces of our partners or kids. Computer screens are utterly ubiquitous frames, their dimensions immutable. And we pile in numerous other frames within them; in some cases frames that are more wily and reliable servants, principle among them for most us being the window[s] we stare into for video calls. These have sparked a vernacular all their own (“Can You Hear Me?” for example) along with ‘share your screen’, ‘your camera is off’ or ‘you got some pants on, officer?’ All these frames move around inside the big one – sometimes the machine makes that decision and sometimes we organise it to suit our needs of the moment. But it’s a rigid, geometric 2D terrain that has its own rules and aesthetics which without most of us really realising is becoming a style all its own all but colonising our consciousness in the process. Naumenko has grasped this concept wholeheartedly and plays with it ceaselessly throughout Can You Hear Me?, crafting a kind of moving digital patchwork quilt in the process.

We saw the first visual whispers of Theodore Ushev’s new film La Vie avec un idiot (or “Life With An Idiot” on the digital drawing board during a visit to the Miyu office in Paris a couple of years ago. It looked pretty good then, it looks AMAZING now. Ushev never disappoints. It’s been a little while between drinks for Ushev but this has been worth waiting for. It is based on a 1980 short story of the same name by Victor Erofeev (also spelt Viktor Yerofeyev). It’s the exact kind of story that Ushev has long relished (think of Blind Vaysha, The Lipsett Diaries and The Physics of Sorrow) and has even been turned into an opera some years back. Ushev is a force of nature. His capacity to animate is almost impossible to fathom when he hits top gear. He has no signature style but some of his films have employed abstracted backgrounds and a movement of characters so rapid that precision of artistry becomes less the imperative allowing the boiling tango of movement to keep our eyes moving and our imaginations trotting along behind, desperately just trying to keep up – and that’s exactly what is happening here.

The almost polar opposite is the case with Autokar by Sylwia Szkiladz. It is a film in which most of the interior meaning of the story, the potential motivations of the characters and the progress of the journey being undertaken by the young girl at the centre of the story is gathered over time from the details and nuances of the artwork. Sometimes these visual cues are front and centre and at other times they lurk partially cloaked behind other characters or parts of the bus. But they do their best work, portray their best meaning and give us the best chance to absorb their meaning and potential when they are given enough time on screen. There is an artistic discipline to getting this just right and in Autokar Szkiladz pulls it off with quiet, confident aplomb. There is not a wasted drawing, an unnecessary frame – everything is there for a reason and the more you see the better the sense of the young girl’s increasingly complicated journey you will build.

Ploo by Jon Frickey on the other hand, is an unashamed visual riot, absolutely revelling in a bold, quirky aesthetic that Frickey stumbled across by accident. He started playing around with something called a ‘Vectrex’ which is exactly what it sounds like – a 1980’s-era home video arcade system sold by a mail order catalogue company. But…….. “little did I realize that what made the Vectrex special was its vector monitor — a now-defunct technology” says Frickey. I think you can probably guess where this is going. “Despite their simplicity, vector monitors are totally mind-blowing (at least to me, in an admittedly super nerdy way) because they translate mathematical data directly into minimalistic graphics, they offer virtually unlimited screen resolution at extremely high frame rates — qualities unmatched even by today’s cutting-edge technology.” Righto, good to know. Now whether that makes any sense to you or not, it absolutely explains the weird and wild way Ploo not just looks but moves. The meta-story Frickey has pulled together to keep this show on the road is – as Cartman might say – ‘hela-hilarious’ and reaches into the very soul of the nerd video culture that spawned it. It’s just a flat-down treat whichever dimension you engage with it in.

Unless you’ve been living under a rock lately, you’ll probably have heard that a man formerly known as [a] prince recently wound up taking a good swift kick in the titles. This came at the end of a period of royal intrigueness and immediately sparked another. Arcane rules, conformist-demanding norms, traditions that hardly bear a form are all part of the mindscape of those that live in that world. This kind of opaque social structuring, and the warped/alternative attitudes that it tends to foster is the foundation that The Golden Donkey by Anne Verbeure is built upon. It’s a beautiful, truly painterly film and that artfulness sits easily with the subtleties of the acting and voice work that tour us through this otherwise oddly discordant community who are all living lives that are anything but beautiful – or painterly for that matter. It’s a visual style Verbeure is perfecting with each passing film (Orlando, Red Giant and now The Golden Donkey). The ‘paint’ fills the frame and gives us that instant hit of visual satisfaction but while we are inhaling that we are probably not as tuned into the often unusual compositional work that is playing out before us, often shrewdly taking control of our gaze and benevolently infecting our pathways of extracting the meaning out of any given scene. Set in a time long ago, it tends to suggest that some things don’t really change that much.

The programme wraps up with Signal by Emma Carré and Mathilde Parquet. It’s maybe fitting that our final competition programme finishes with a puppet animation because there is just so much great puppet animation around at the moment. It requires its own ‘mise-en-scenery’ mindset to make puppet films like this work and there are some great examples of that mindset in Signal. The idea to set some of the early action in a circular space observatory allows for some very rich manipulation of scenery that you just can’t pull off in a square room. Staging some of the action in a noirish dark/spot lit set gives a particular focus to those particular characters and somehow, in some weirdly inexplicable way, makes it OK that a band of musicians to fade up out of the gloom as a backing band for a scientific presentation which, in turns, perfectly sets the stage for the space opera musical that rolls outs out momentarily. It sounds like a bit of a jumble but it is so so not – it’s just the opposite, it’s the kind of rollicking narrative flow that animation can do so well.

Mise-en-scene…eh! Where would we be without it!

Malcolm Turner

International Competition Programme 8: Long Shorts screens at The Garden Cinema Sat 6 Dec and online from the same date (available for 48 hours)

Leave a Reply