Time to talk about time

“Yesterday’s the past, tomorrow is the future but today is a gift. That’s why they call it the present”

Bill Keane: Cartoonist (The Family Circus)

Time! It’s a uniquely human edifice. It’s a uniquely human concept. It is one of the most potent and one of the few truly universal ingredients of the human creature. By all accounts (well, by most accounts) we were hardwired to get our heads around the notion of time before we developed proper language skills. Back in the day, we might not have been that flash on the barista skills or too handy at putting together the flatpack wardrobe but we did notice that the length of the days seemed to vary and that the moon in the sky seemed to have some rhythm going on.

“They say that comedy equals tragedy plus time. I’ve got to the point where I need more time … but I’ll settle for less tragedy”

Jon Stewart: signing off from ‘The Daily Show’ in 2015

Here in the UK, being able to keep an accurate track of time became important when trains started linking towns. Until then, the biggest, loudest clock in town (usually on a church or town council building) was basically the law as regarding what time of the day it was. They wouldn’t have gotten away with being wildly out of sync with the sun but evidence was that the time in different towns could vary by a surprising amount. This variation didn’t really matter that much – until a fast and scheduled travel system started rolling. Suddenly, everyone had to be on the same time or they’d miss the 12:19 to Wolverhampton or the tinder date would assume they’d been stood up and bail.

“Time you enjoy wasting is not wasted time”

Marthe Troly-Curtin: Novelist

How many songs are there about ‘time’? It’s probably only second to how many there are about love stories gone wrong or – occasionally – right. Often there’s a cross over….. a siren plea to have time already spent back again to put past mistakes right. Many songs dig deeper into the philosophy of time and how it defines our life and life stories. Examples abound but perhaps one of the more iconic would be the Pink Floyd song simply titled ‘Time’.

“The reason it’s a good song is because it describes the predicament of anybody who, growing up — if we’re grown up at all — suddenly realises that time is going really, really fast,” says Roger Waters, the Floyd member who wrote it when he was 29. “It makes you start to philosophise about life and what is important and how to derive joy from that.”

“No such thing as spare time, no such thing as free time, no such thing as downtime. All you got is a lifetime.”

Henry Rollins: best known for being Henry Rollins

Music creates pictures of how time is emotionally consumed and heart-breakingly lost. But movies depict time. They can offer pathways to shifting time around to suit the story, cutting and pasting time in or out at the whim of the director. Almost every sci-fi film is going to have this baked into its core premise. But so too do more prosaic variants such as costume dramas or some blockbusters of the ‘Back To The Future’ ilk.

“They say that time changes things, but you actually have to change them yourself”.

Andy Warhol

But animation goes a step further – a big step further. Animation is made out of time like bread is made out of flour or holy cheese is made out of swiss. Sure it takes a long time to make a movie; several months can go into just shooting the footage needed for the two hours that will make it to screen. And although the ‘hurry-up-and-wait’ ethos permeates the production process for so many of the people working on it, there is still something happening all the time. But while any given 20 second scene might hijack hours to set up for and 20 takes to get right, ultimately what is used is a ‘real time’ recording of people doing and saying something.

None of this is true for animation. Animators paint with time.

“Until we can manage time, we can manage nothing else.”

Peter F. Drucker: Author, educator

Sure, their films depict whatever passage of time is demanded by the narrative arc of their story just as live action does but animation takes a long time to make and the pathway to controlling how any given 20 second scene ultimately works is not to direct the action for the right 20 second ‘take’ but to spend many, many times that amount of time marshalling a range of skills and managing the variables of their real lives’ varying moods and energy levels in a way that still allows the scene to feel like the fleeting moment of time in the film that it is.

This reality, combined with the very essence of what good animation can, and is ‘allowed’ to show has a material impact on the way so many animated films weave the essence of time into the fabric of their stories. And in turn this tends to mean that animated films often present that ‘feel’ of time in ways that match our deepest and most ethereal human connections with this most precious of all products.

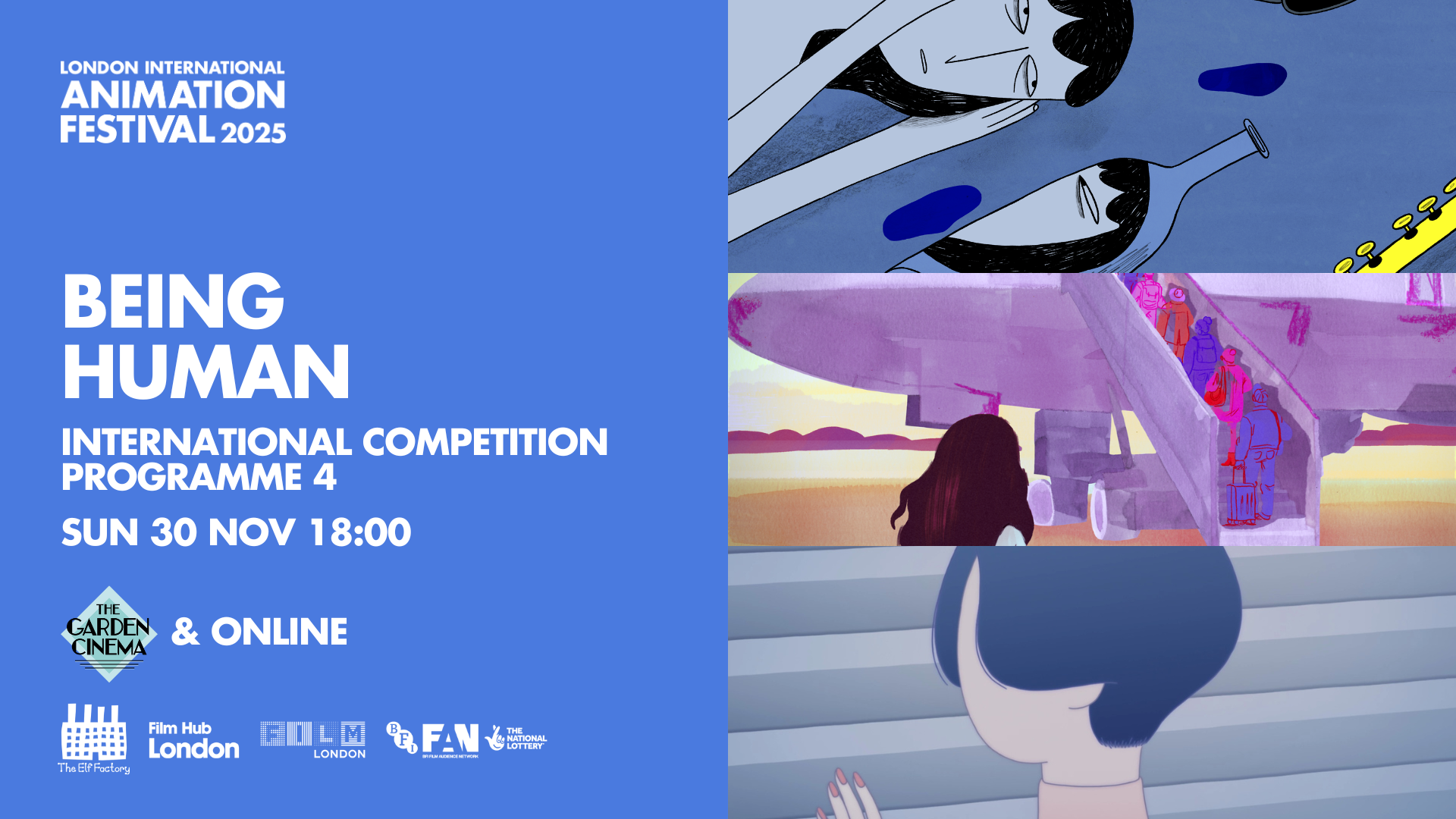

It’s little surprise, then, that a number of the films that do the very best job of this should find themselves sharing the limelight in LIAF’s Being Human programme.

The concept of ‘time’ sits in the very middle of the opening film Retirement Plan by Royal College of Art alumni John Kelly. As indie animated shorts go, it is a film that has attracted a remarkable amount of press and attention. Taking out the Grand Jury AND Audience Awards at the last SXSW Animated Shorts competitions didn’t do its profile any harm and among the plethora of press commentary it has received, moviejawn.com probably summed it up best with “in seven minutes Retirement Plan makes one feel all the feels”. And it does. Pin-balling around between poignant, hilarious, insightful, reaffirming and thought provoking, it is a film that dreams about how better times ahead are going to be spent whilst simultaneously insinuating that the times already spent may not have been put to best effect, leaving a yearning to fulfil passions large and small that went long unfulfilled. ‘Ray’, the central figure in the film, spends most of his time talking about and contemplating how he is going to make best and most use of the time that will be the closing chapter of his life and although he is not looking in the rear view mirror at the life he has already lived, hints bubble up here and there and you wonder if he’s not just occasionally a little lonely.

Loneliness is tackled front-on in Marta Reis Andrade’s new film Dog Alone. It is actually three true stories woven into a single flowing narrative and plays as an affecting reminder that loneliness is felt and addressed in very different ways. The stories of the key humans in the film, one an avatar for Andrade herself and the other a character based on her grandfather, are plain enough to see and relate to. Many of us will have had similar periods in our lives that parallel Andrade’s own loneliness whilst living in a large city in another country far from family and the little familiarities that make a house a home. Likewise, many of us will have watched an elderly relative slowly recede into an internal world that contains many of the people and memories that make that world fuller than the one they are living in. But the dog is a more mysterious and unpredictable presence, alternating between something akin to a foreboding ghostish spirit and a figure into which we can pour our simple, unfiltered sympathy. The dog, too, is an avatar, based on a pooch who lived next door to Andrade’s family home in Portugal and spent much of its days howling in loneliness at being the last of five dogs who had once lived at that house.

Marko Mestrovic’s new film, simply titled How poses more questions than it answers. Actually, to be more accurate it asks only one question – how? – and offers no answers whatsoever. “I want to place the viewer in the role of the one who wonders, inquires and who opens themselves to an answer – which the film never offers, but the viewer may arrive at for themselves”, says Mestrovic, making it clear that this was a deliberate and key focus of the film. Densely packed with a non-stop parade of mental, visual and narrative micro-provocations that ensure the audience plot their own path through, it is a film in which no two people are likely to have the same experience watching and contemplating. While that is true to some extent of almost any film, it is the raison d’etre that is the beating heart of this one and in a lot of ways has more in common with poetry than narrative-inflected storytelling. It probably comes as no surprise that Mestrovic believes that poetry and art “offer the only lifeline to the human mind”.

For most of us the main vehicle to archive our memories with is the camera on our phone. The sheer volume of the photos and mini videos and their overwhelming ubiquity has, to some minds, diminished their worth as time capsules and retainers of something deeper than a quick, shared view on the fly. This was not always the case and the cost and more elongated clumsinesses required to actually take, make and keep a ‘photo’ tended to bake into them not so much a greater value per se but perhaps a somewhat different one. The ‘time capsule’ ingredient that kick started Speeding, Of Course was a recorded interview that one of the filmmakers, Joonatan Turkki, found of his father. It resonated with him to the extent that he actually turned it into a radio play which, in turn, inspired Anni Sairio to propose turning it into an animated film….. and here we are! It is nothing short of a joyous masterclass in the arts of cut-out and stop-motion animation, channelling the humblest of ingredients – paper, cardboard and an analogue voice recording from another age – into a celebration of a life well-lived and the joy that can be gotten from the simplest of inspirations.

Looking back through time and attempting to reconstruct a picture of somebody from the various fragments of them that manifest in the mind of the rememberer is the fluid, flexible and imperfect tide upon which Poppy Flowers floats. Made at Estonia’s EKA school by expatriate Cypriot artist and animator Evridiki Papaiakovou, it’s a dark but rich tapestry of imagery beautifully crafted in the ‘scratch-on-film’ style, riven through with hints of filmmakers such as Marie Paccou, Paul Bush, Regina Pessoa and even a few visual twists that seem to suggest a couple of the lessons passed down through the ages by Viking Eggeling.

And our ‘Being Human’ programme ends large, loud and unashamedly hilarious. Job, Joris and Marieke are back!! Their current film Quota offers up not just one possible idea to manage the climate crisis confronting us but the riotously comical implications for ignoring the disease and the cure. Only Job, Joris and Marieke can make a film that looks and rocks along like this and deliver up such mirthful carnage. Taking this particular route is not just the reflexive creative instincts of the Job, Joris and Marieke team but also a deliberate way to ensure the climate message embedded in the film had the best chance of being received by the audience.

“We didn’t want to make a preachy film because no one wants to see that”, says Joris.

“And by giving it a funny and bloody twist, we found a way to tell the story,” adds Marieke, with just a hint of glee in the eye.

Despite the comedic imperative driving the narrative of the film, it still brought up some interesting and key questions of the type that tend to sit at the heart of – and often clog the gears of – the debate on how to address climate change. For example, if you eat meat, do you start calculating the carbon emissions when it is grown, when it is turned into a consumable product, when you buy that product or when you eat it?

It’s an issue the trio take very seriously – so seriously in fact that they didn’t attend the world premiere of Quota at TIFF last year because they didn’t want to fly. Whether or not the quirky idea offered in the film could ever be put to use, the bigger message is that we need to do something…… because we are running out of time!

Malcolm Turner

International Competition Programme 4: Being Human screens at the Garden Cinema Sun 30 Nov and online from the same date (available for 48 hours)

Leave a Reply