Let’s take a different approach to introducing LIAF’s annual showcase of abstract and experimental animation this year. We want you to meet somebody who helped get us to where we are right now.

Valé Leonard Lipton.

A lot of you probably do not recognise the name but all of you will know of at least some of his work. Leonard Lipton left us on October 5th earlier this year. Among his various contributions to the greater good was an unparalleled understanding and documentation of the history of cinema and the panoply of machines and devices that have brought us the moving image in so many of its glorious variants over the decades.

Actually, over the centuries. Lipton was the one who – in many ways – brought the history of the magic lantern into the realm of our understanding of the origins and aesthetics of ‘cinema’. Before Lipton, most scholars had decided that the dawn of photography and motion film rested upon the inventions of Louis Dagueurre who produced an early form of reproducible photographic imagery that was known as the ‘daguerreotype’.

A few wild and crazy mavericks from the academy made the scurrilous claim that a weird process invented in the early 1800’s by one Thomas Wedgwood (Charles Darwin’s uncle, no less) was a form of real image capture. It was (probably) but the evidence is hard to weigh in this day and age because Wedgwood’s method didn’t include any form of ‘fixing’, meaning that the image disappeared off the plates upon which it was created almost as quickly as it rose into view…. meaning that the evidence was probably hard to weigh the next day, let alone 200+ years later.

Lipton, though, looked at the big picture, so to speak. Over years of research he had gathered an encyclopaedic knowledge of – among so many other things cinematographic – magic lanterns. This included a close study of the very first magic lantern made all the way back in 1659 by the Dutch inventor, Christiaan Huygens. It’s a connection that makes sense to us now but before Lipton, not very many people knew much about these devices nor did they join the dots between them and the notion of people sitting down to enjoy a collection of still images strung together to present something bigger than the sum of its parts.

Lipton’s thirst for an understanding of the ‘machines’ that made and projected moving images was just simply immense. In 1980 he founded the Stereo-Graphics Corporation that produced a form of ‘flickerless’ 3D stereoscopic projection: it was used in more than 80,000 cinemas worldwide. He worked on something called ‘molecular modelling’ which was put into service on the Hubble space telescope. He held more than 70 patents for this stuff and was honoured by the Smithsonian Institute for a lifetime contribution to the world of cinema.

And he wrote books. Great books! Arguably the best of them was ‘The Cinema In Flux: The Evolution Of Motion Picture Technology From The Magic Lantern To The Digital Era’. Page turner. There is so much in this book that explains the evolution of abstract animation. It outlines how the limits of early moving image making machines fuelled the imaginations and experimentations of people who sought not to capture renditions of real world images (live action) but to bring to life imagery they carried in their minds and wanted to see dance and move on a big screen.

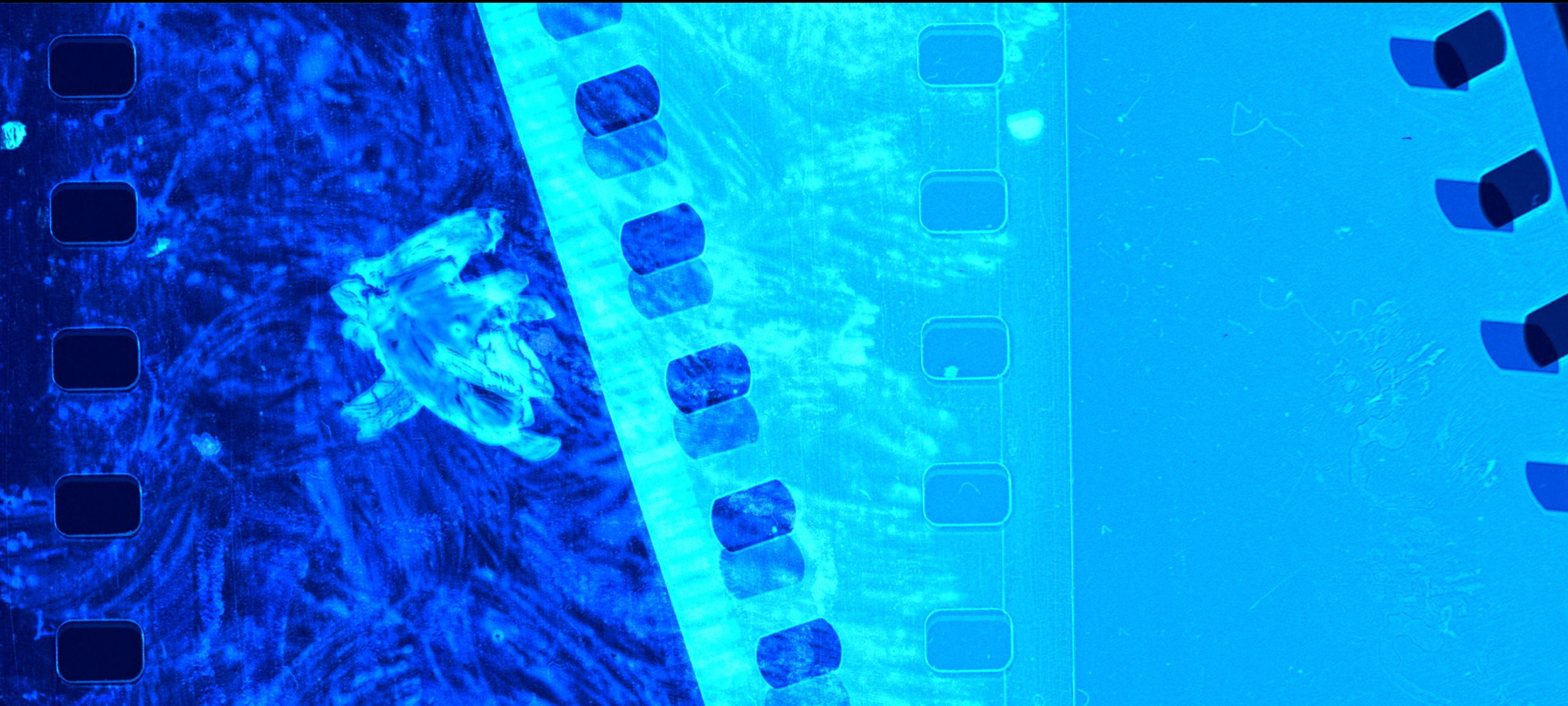

This is a rich, utterly absorbing history and the rules these early experimentalists crafted form the platform for the films in this programme. An obvious example, of course, are the early cameraless films of artists such as Len Lye and Norman McLaren, who had access to film but not to cameras. Although producing ‘narrative’ or ‘representational’ imagery by scratching images one by one directly onto film stock is possible, it’s difficult to make the imagery compelling or complex. Abstract imagery, on the other hand, is the perfect content.

The cameraless animation aesthetic – if not the actual technique itself – is a lot more enduring than many people might think. In fact, it perfectly bookends this programme by featuring the work of two of the working maestros of the form (both Canadian), Steven Woloshen and Richard Reeves whose films respectively open and close this year’s Abstract Showcase.

Woloshen’s Perf Dance is a continuation of his work harnessing digital technologies to progress and expand the creative boundaries of cameraless animation.

Reeves’ film Intersextion, on the other hand, is a slam-dunk reminder of the viscerally textural visuality of abstract images painstakingly hand-etched directly onto a strip of 35mm film, frame by frame. In so many ways, it channels his 1996 masterpiece “Linear Dreams” and it will look simply superb on the big screen.

It will come as no surprise to the LIAF faithful, but the world of animation – the big, wider world of animation – is not utterly dominated by CG or computer generated animation. That truth starts getting starved of oxygen pretty quickly when it tries to escape the realm of the animation festival world though; as does even the realisation that there is such a thing as ‘abstract’ animation. But Lipton lays out a whole different savannah of how both computers and the development of abstract animation are inextricably interwoven.

In fact, in the earliest days, abstract animation was the only moving imagery that computers could create. Lipton traces an ancestral path through early military experiments that could produce representations of missile flight paths (arguably the first computer generated abstract animation) to a much longer, more fascinating and more nuanced history in which large corporations who had an intuition that ‘computers’ might be worth looking into had few choices other than to turn to artists to try and get these beasts to produce anything at all.

Back in the days when a mouse was a rodent or an Anaheim souvenir, just trying to ‘communicate’ with these things was the first battle. In 1951, the wizards at M.I.T. created a crude form of ‘light pen’ that let them create a series of dots that they did their best to entice a computer to join. The SAGE computer they developed that allowed this dot-joining barn dance to take place would have struggled to fit into cross-channel lorry.

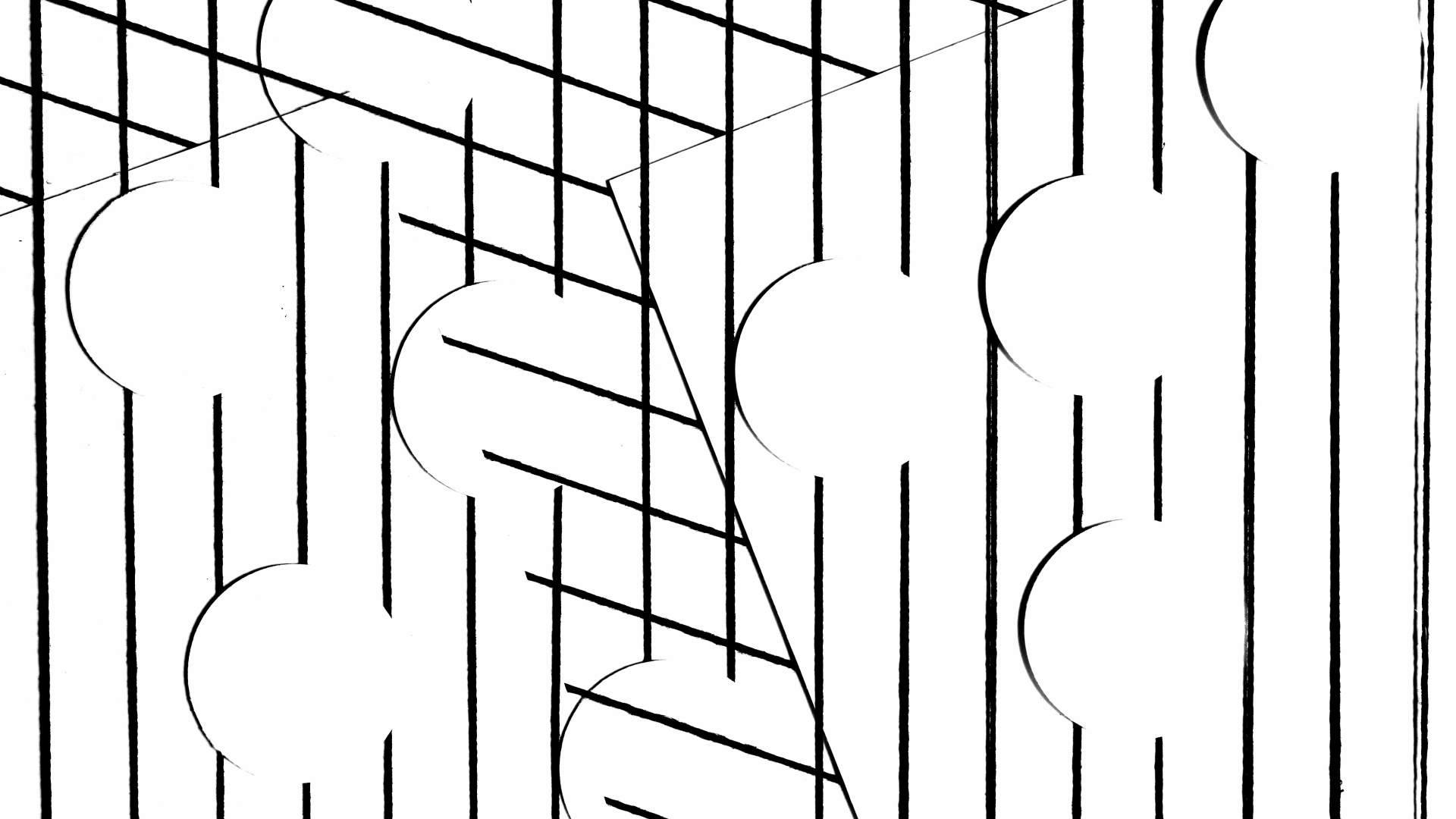

Bell Labs (the original American telecom behemoth) built an entire facility and turned it over to artists of the like of Frank Sindon, Edward Zajac and Michael Noll. The inmates were running the asylum. Lipton reminds us that Michael Noll’s “Hypercube” was revealed in 1965 and was deemed to be a revolutionary work of moving image art. The common thread that ran through all of the work being created by this happy gang of CG pilgrims was an aesthetic based almost entirely around drawing lines between dots. Colours were impossible, curves more or less so. This was an aesthetic driven by the limitations of the machinery of the day. And yet, it is an aesthetic that permeates the creative impulses (realised or not) of so much abstract animation to this day.

Ruled Surface by Pete McPartlan is a grand example of how this style of animation has evolved over the years (although am I the only one who catches glimpses of the Viking Eggeling’s ground-breaking 1924 Symphonie Diagonale?). And if this instinct underpins the creative energy of Unreal Central by Junien Cho, Qingmei Melody Li and Yung Ka Valerie Mak it is absolutely supercharged in Reka Bucsi’s Intermission, a remarkable return to the screen from the maker of the astonishing epic Solar Walk (2018) which was almost too much to take in.

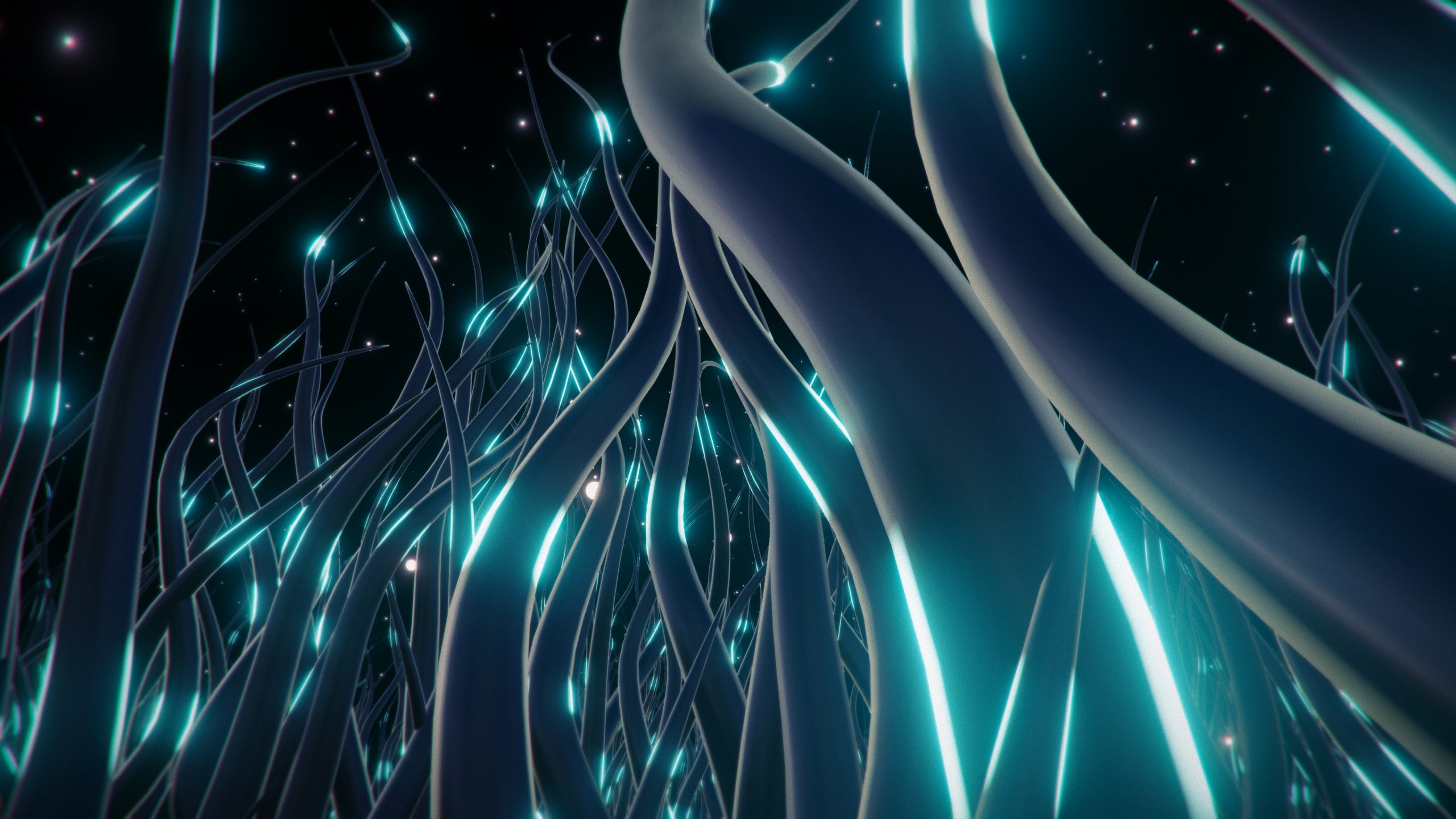

Lipton reminds us too of the weird engineering that went into moving image making devices that weren’t cameras. Primary among them would have to be the whirring sculptures of John Whitney Sr who concocted machines that looked like the misshapen escapees from a basement holding the banished rejects of Alexander Caldwell’s worst ideas. Some of them were made – literally – out of US missile launchers that Whitney bought at army surplus stores. Gotta get me one of those! These things ‘drew’ arcs and images in thin air that Whitney captured in a variety of ways and transformed into abstract films that could be viewed in a cinema. In fact, the first piece of ‘abstract animation’ that the majority of people ever saw was by Whitney and created on one of these things: it was the title sequence to Alfred Hitchcock’s 1958 classic Vertigo.

This introduction of curves did not just change the look and expand the visual potentiality of early abstract animation making devices, it created and empowered a whole new style and – with it – a kind of visual rhythm with which abstract animation could be imagined in the first place. This, too, informs many contemporary films and infuses our annual Abstract Showcase with its lineage.

Elements of Sphere by Wataru Iwata and Sacred Clockworks by Moritz Schuchmann would seem to carry at least a little of this DNA.

The machines and the devices that are used to create abstract animation are – of course – only a contributing factor of their creative structure. But the influence of the invention and development of them is fused into the genre – and long may it be so.

Lipton reminds us of that; charting in incredible detail the nuts, springs, washers and skinned knuckles of the technologies that gave us “cinema” as a whole. And if that strikes you as something that is worthy in and of itself but not quite matching the original claim that “we all know at least some of his work”, well……..

One day Lipton, a budding poet, sat down at a typewriter and tapped out:

Custard the dragon had big sharp teeth,

And spikes on top of him and scales underneath,

Mouth like a fireplace, chimney for a nose,

And realio, trulio, daggers on his toes.

The typewriter wasn’t his though, it belonged to Peter Yarrow, who was a housemate of Lipton’s friend. Peter Yarrow was studying physics at the time but would go on to join Mary Travers and Paul Stookey who are better known as Peter, Paul & Mary. Yarrow loved the poem, tweaked it a little and – ding ding – like an arc drawn in the air or a bunch of dots joined to make a line “Puff The Magic Dragon” was born. There was, apparently, another verse to the poem in which Puff found another little boy to play with but Yarrow misplaced it and Lipton couldn’t remember the words.

It mattered not, the royalties funded several years of dedicated research into the history of cinematic inventions.

Some days are diamonds!

Leonard Lipton. May 18, 1940 – October 5, 2022

by Malcolm Turner

Abstract Showcase screens at The Garden Cinema and online Sat 26 Nov find out more